Berlin Atonal 2014 // Berlin Atonal

Coming more than two decades since it’s last incarnation, Berlin Atonal was back for a second installment since it’s reemergence in 2013. Originally held in Kreuzberg’s acclaimed SO36, the festival was host to the likes of legendary innovators Einstürzende Neubauten, Test Department, 808 State, Psychic TV and many more. These artists are now something to the effect of household names in the city, but were at the time just seedlings of the bubbling underground scene that was about to go massive. In this respect, little has changed about Atonal; the festival continues to herald pioneering musicians and artists who will themselves become luminaries of the scene in turn. Furthermore, unlike most summer festivals, an achingly meticulous program bound Atonal’s style and aesthetic, such that nothing feels out of place, and not one artist from the impressive roster clashes with another. With the quality of artists set at such a dizzying height, it would be near impossible to give justice to each, instead here is but a few of my highlights…

##20_08_14##

The first thing that hits you about Atonal festival is the titanic mass of the venue. Despite having seen Kraftwerk before – it's located above the legendary Tresor club – the building is hard to get used to. Kraftwerk stands alone as a stunning monolith of metal and concrete that externalises the cold, hard music played within. The sheer awe factor that Kraftwerk gives upon entry is already enough to give it a special place in my heart; this is a festival that values the charm in the things that most find ugly, from the music to the all too oft-misunderstood Brutalist architecture. This is a festival without face paint, pie-eating contests or campfire songs. Instead, noise, chaos and darkness are given a special precedence by the festival and are encouraged to be explored in every respect.

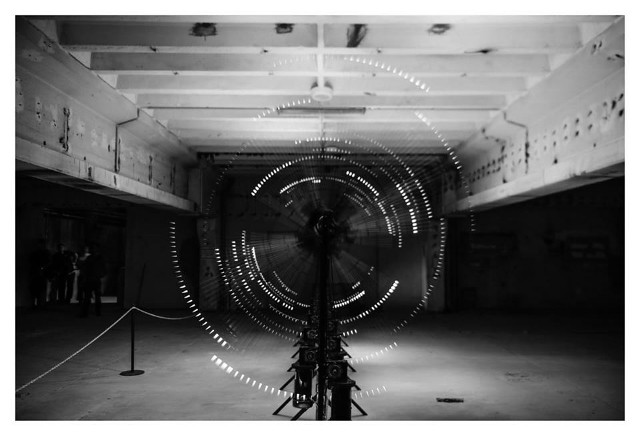

This can be said not only of the music but the long list of intriguing installations as well. What is made quite clear is that despite Tresor's notoriety as a space to dance in, Atonal situates itself closer to the art-exhibition ethos of music, meditating seriously on the nature of sound, not just moving to it. It wouldn’t be fair to refer to Atonal as simply a music festival either, as the visual dimension was given as much thought and consideration. A particular highlight, ‘PARSEC’ - a kinetic audio-visual installation within one of Kraftwerk’s mysterious side rooms - encapsulates the same psychological effect of much of the music played at the festival. Sixteen identical metallic arms oscillate around a central cylinder, creating a hypnotic and haunting vacuum of light and sound. I thought to myself how strange it was to have such a modern piece placed before a Steve Reich concert – what was the connection? – until it struck me; both Reich and this exhibition, and indeed much else that was on this week, work upon the principle that composite parts can create harmony, no matter how weird and seemingly chaotic they may be by themselves. A documentary on modular synthesis, ‘I Dream of Wires’ grounded this gestalt notion in its historical lineage from Moog to Throbbing Gristle to the modern DJ, exhibiting the myriad ways in which a analogue synthesizers managed to create musical unity from internal random fragments. Thomas Kircher, who introduced the film, later invited audience members to attend a free workshop at Schneidersladen, Berlin’s modular synthesis store, where guests were freely encouraged to indulge themselves in playing with these beautiful machines.

The first piece of the music played at Kraftwerk was a befitting choice. Steve Reich’s ‘Drumming’ takes the rhythms and timbres of Ghana and recontextualises them within his minimalist project. The piece had an altogether more commanding effect when backed by the cacophonous natural reverb of the room, and this was intentional. Atonal itself recontextualised Reich as one of the fathers of inspiration for much of the repetitive electronica that dominates Germany today, tracing its ethnomusicology from the open spaces of Africa to the bustling streets of New York and finally coming together in this vast power station. However, the crowning piece of the evening was Reich’s ‘Music for 18 Musicians’ (potentially my favorite piece of music ever written.) It sounded different than my first listen as a random selection on someone’s Ipod in a Brighton chip shop, or on the 12-hour bus journey from Toronto to New York. Both hold a special significance to me, but both times I listened alone. By contrast, this was the first time I had heard the piece in a group, with everyone there held together by a shared passion for hypnotic repetition and structure in music, collectively reflecting on previous times they had heard it. For those who had never heard it before can now cite Atonal for their first time.

##21_08_14##

Speaking with Dscrd earlier this month was more than enough to tantalize myself into giddy excitement over their performance on the first official day of the festival. Despite speaking with them personally, so much of their live set up was still a mystery: why was there five of them? What exactly were they doing on stage? The truth is, Dscrd function as a hive-mind – their answers to my questions were not delineated as one person over another, but as a single 5-letter unit: Dscrd. This mirrors the visual themes during their set – surveillance footage and security cameras presented the hive-mind mentality of consumerism, giving the audience the unsettling Foucaudian panoptical perspective that was the subject of Dscrd’s latest EP.

Persisting the morbid manner of the evening, Miles Whittaker of Demdike Stare fame took the sound to somewhere altogether more psychedelic, showcasing his rich library of middle-Eastern samples and setting them against the backdrop of moody synthetic experiments. However, it was Sendai and The End of All Existence that exacted this science most concretely, slowly painting the concrete slabs of the room with waves of entrancing dub tones, each more dank than the last. What began to come clear throughout the evening is that the homogeneous sound of the festival was not tied down to what people expected to hear in a space like Tresor – I heard not one 4X4 kick for the first two days – rather, the festival was carving out a new space for itself that was wholly unfamiliar, and Berlin had not lost the spearheading, innovative climate that it was rightfully best known for.

##22_08_14##

The third day of the festival found its direction shifting slightly away from its cerebral leanings, and instead honing in on the more visceral, physical side of music. Headless Horseman’s remorseless electro workouts overhead sounded all the more menacing on Kraftwerk’s mammoth sound system, while the seizure inducing visual display washed over the stunned audience. The atmosphere was one of immense anticipation, as the first after party at Tresor was round the corner.

Free admission to Tresor on a Friday night is a significant luxury; although somewhat distinct in its approach to music from Atonal, the stunning concrete labyrinths that snake around beneath Kraftwerk make for a similarly intoxicating and psychologically intense experience. The notion of being ‘lost in music’ is rarely truer than in Tresor. With perhaps the exception of Berghain, there aren’t many clubs that are better suited for a festival after-party. A particular highlight included Pinch’s unexpectedly eclectic mix of percussive electro that sounded like oddball versions of some of the UK Bass music from the last two years, only darker and deeper. To close, Jonas Kopp brought the night to its knees with three hours of unceasing, no-nonsense techno tools that shook the walls out of their foundations until 10 in the morning. I left with little of my mind in tact.

##23_08_14##

Day four was host to arguably the most anticipated event of the festival: the first live performance from Cabaret Voltaire in over 20 years. Their new style was striking; gone were the overdriven post-punk pop jams of the 80s and in its place was super-modern hi definition noise, with nods to tribal techno and even jungle. Despite being from a conspicuously earlier time than most of the artists on the roster, CV delivered what was some of the most futuristic sounds of the entire festival, with an unmistakably modern sheen.

Following on from the grainy, metallic sounds of CV came a performance from FIS in stark contrast to what came before. Now, the sonic palette had a distinctly naturalistic timbre, with ripples of tremolo lapping around the stereo field like a swirling cyclone of dead leaves. Neel – one half of Voices from the Lake - powered the night through with a set of achingly minimal techno-function tools in Tresor, often with nothing but a kick and mazes of tripped out modular synth lines and alarm sounds. Without a doubt the most impressive techno set of the week.

##24_08_14##

London-based Helm opened the ceremonies for the final day, providing a disquieting set of earthy drones and chilling textures. In contrast to much of the festival’s previous sounds, Helm used distinctly acoustic instrumentation – rocks, glass, Tibetan bowls – cranking the amplitude so loud it felt as if an eardrum-bursting clang was just round the corner: an affective method for instilling fear into an already unsettled audience. UF – a brand new collaboration between Samuel Kerridge and Berlin duo OAKE – didn’t give the audience much solace either, as momentum built towards the climax of the week. Although considerably more synthetic in tone than Helm, UF shook the room with equal weight, delivering pounding, off-kilter kicks, heavily textured noise and even cold-blooded screams at deafening volumes.

This was, in a way, a final surge of the ‘Atonal sound’. What would come next would be two legends of their respective fields; Tim Hecker and Source Direct. Since 2013’s phenomenal _Virgins, _Hecker’s sound has centered on building endless layers of scattered and fragmented components. Hundreds of splintered pianos and organs sounded as if they were being slammed into one another in the venue by a poltergeist, creating an intoxicating hall of mirrors effect where different sides of the room echoed subtle variations of the same original resonances. These were supported underneath by thick static drones - almost too thick for the speakers - filling every nook of space in the venue. Indeed, Hecker’s set sounded better than anything else I had heard in the building, and seemed to turn the already ghostly space into something of a haunted house. The choice to place Hecker as the penultimate act on the final night was a perfect choice, as audience members were given space to reflect on their week before the final rave commenced...

Legendary drum & bass outfit Source Direct was an oddly appropriate choice to close the festival. Although I had heard almost nothing in this vein before at the festival, the rough, sonic assaults of early jungle felt right at home in Kraftwerk, and shook the bones of all those watching, giving the venue a lease of life not seen before all week. Despite Atonal’s antithetical approach to music making and art more broadly, I couldn’t help but smile when the house lights had been up for at least half an hour before Jim Baker was done delivering his set of jungle classics.

Part of me finds it mildly embarrassing that Atonal fits, to such an alarm detail, the mold of how I would put on a festival. Is my taste really this predictable? But then another, less narcissistic part of me, accepts that Atonal is simply hitting the nail squarely on the head. Not just in the selection of music, but the visual arts, the venue, the name and everything that name represents.

- Published

- Aug 27, 2014

- Credits

- Words by Georgie_McVicar