Echo Spaces // Radiophonic Workshop

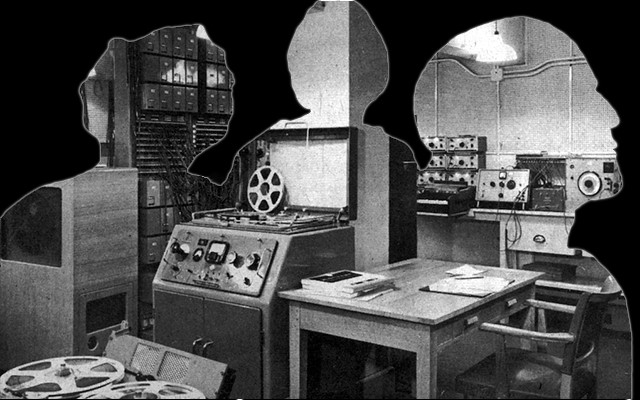

Founded in 1958, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop has left a legacy difficult to rival. A year prior to its establishment, composer and sound engineer Desmond Briscoe had worked alongside Daphne Oram - another composer and later creator of the 'Oramics' machine - on a number of radio plays. These included Samuel Beckett's All That Fall and Frederick Bradnum's Private Dreams and Public Nightmares.

Such was the public interest in the so called 'radiophonic' sounds Briscoe and Oram created for these plays, the workshop was established by the BBC with the expressed interest of creating both new music and sound effects for radio. By the time it's legacy was complete however, the Radiophonic Workshop had exceeded these goals tenfold, tagging, either directly or indirectly, some of the most notable advancements in British electronic music.

Many of these developments would relate to a movement that had been initiated earlier in Paris, with the advent of 'Musique Concrète'. Oram in particular would explore the possibilities of tape manipulation, looking to new techniques to create the strange, haunting and otherworldly sounds the Radiophonic Workshop became best known for. Conventional recordings would be spliced, reversed, stretched and otherwise processed in any way possible.

One of the most famous uses of this technique came in 1963 from a woman named Delia Derbyshire. Derbyshire was born into a working class family in Coventry in 1937, and went on to study music at Cambridge before joining the BBC in 1960 (not before being turned away by Decca Records in 1959 on the grounds that they did not employ women). After working for the corporation as an assistant studio manager for two years, she was assigned to the Radiophonic Workshop, where she would work on an electronic realisation of Roy Grainer’s Dr Who theme. Alongside the now iconic soundtrack, Derbyshire would also help devise sound effects for the programme, for example using manipulated recordings of a set of keys and a broken piano to create the sound of the Tardis travelling through space.

Despite the impact of her work, the BBC never credited Delia for her contributions to Doctor Who, nor was she ever issued with royalties for her role in creating the soundtrack and related effects. Derbyshire left the Workshop in 1973, in her own words, in the interest of "self-preservation".

The Radiophonic Workshop closed in 1998 as it was failing to generate enough revenue, however 2012 saw its revival as an online entity, fronted by Matthew Herbert and supported by both The Arts Council and the BBC. To celebrate its legacy, we decided to take a deeper look at three of the Radiophonic Workshop's most influential members.

###Daphne Oram // Founding Studio Manager

Despite being the individual that all Radiophonic Workshop roads lead to, very little music from Daphne Oram actually exists. She began as a Music Balancer for the BBC in 1943, and quickly became interested in producing electronic music that used pre-recorded instruments and the radio equipment from the BBC studio. After the successful commission work for Beckett, the British public became ravenous for her novelty electronics and thus, the BBC opened the Radiophonic Workshop, with Oram at its helm. Here, Oram played endlessly with sound; splicing tape and modifying technology to create music which was wholly novel at the time. Yet, within less than a year of the workshop's opening, Oram had left, apparently unhappy with the lack of enthusiasm the BBC showed for her wild synthetic experiments.

From here, Oram pursued her true creative calling: the development of the Oramics studio. The eponymous 'Oramics technique' created sound, not from electronic generators or instruments, but from drawing graphs onto 35mm film, modulating the signal given to the photocells. Surprisingly enough, this technique has a timeless quality to it, and the eery swells and washes that were produced by Oram in those early recordings continue to astonish. The only existing Oramics machine was briefly shown at The British Science Museum in the early 2010s, and was described by the museum's curator, Dr Tim Boon, as being "as important for electronic music as the models of the Great Eastern Ship are to the history of maritime engineering."

I think the few recordings that exist of Oram continue to hold our attention for two reasons. Firstly, the sheer technical prowess of Oram is enough to gawk at: tape manipulation and 'drawn-sound' are techniques that are still used and considered 'experimental' today, and yet Oram was there half a century before anyone else. But more than this, the music itself has an atmospheric pull like no other. Imagine a fastidious Oram locked away in her studio in the small hours, playing with synths and samples, and creating music that sounded like it was written for alien consumption only. There's also a humour to it that is often overlooked. She frequently cut-up and looped extracts from radio advertisements until they sounded absurd and meaningless: perhaps an early critique of the discomforting reality of consumer culture, but also perhaps not... Just listen to this proto-dub extract from 'Birds of Parallax' (on the Oramics compilation), and trace her influence all the way through Kraftwerk, Pink Floyd and Madlib.

Words by George McVicar

___________________________________________________________###Delia Derbyshire // Studio Manager & Composer

Perhaps the most famed member of the Radiophonic Workshop, Delia Derbyshire produced some of its most innovative and intriguing work, and has rightly earned the reputation as a key figure in introducing electronic music to popular culture.

Arguably her finest work, was a series of radio plays that she produced in the mid sixties in collaboration with composer and playwright Barry Bermage. The series was entitled ‘Inventions for Radio’, and each of the four programmes interpreted a different theme – dreams, ageing, god, and the afterlife. Combining cut up narration and droning, pulsing electronics, the programmes eschew conventional linear narrative and attempt to represent the theme or topic at hand in terms of sensations and mood.

Dreams is the first and most unsettling entry in the series. Recordings of people recounting nightmares in which they have been chased, fallen, drowned, or encountered formless Lovecraftian horrors, are paired with dissonant electronics to disquieting effect. Appropriately enough, this recording soundtracked one of the most dream-like waking life experiences I have stumbled into: a surreal oneiric episode in a subterranean public toilet in Bristol. On a springtime visit to the city several years ago, I had been listening to Dreams on headphones as I perambulated around the city centre, and when I descended to an underground Victorian era bathroom to relieve myself, the waves of drones and cut-up voices narrating half-remembered nightmares had shifted my consciousness into a quasi-hypnagogic state. The bathroom was apparently empty, and so I kept the headphones on in the cubicle, happy not to have the presence of another person intrude on my reverie and jolt me back to the real world.

After a couple of minutes I thought I heard a knocking on the wooden stall divider next to me, but thought nothing of it until a head suddenly appeared underneath the door in front of me. A man’s face with long unkempt hair and a straggly beard was staring up at me, not particularly threateningly, but given the situation whatever the facial expression was it was going to make me somewhat apprehensive. Still entranced by the recording, I didn’t react with shock and didn’t even think to take the headphones out, and moments later the head had gone. I sat there bemused for 30 seconds or so before the head reappeared. This time it tried talking to me, but unable to hear over the recording I stared back for a few seconds before swinging at it. The head swerved out the way and disappeared. When I left the cubicle a few minutes later there was no sign of anyone, and as I climbed back up the stairs and into the light, I was left wondering if it had really happened at all, or whether this unanticipated interloper had been just a fanciful creation of an over-stimulated imagination.

What would have ordinarily been an unpleasant and alarming experience became an amusing, somnolent interlude, like a compelling bad trip. I was struck by how the mind needs only the slightest coaxing to break from mundane ordinary experience into something quite different, and this seemed a perfect endorsement of Derbyshire’s attempt to recreate dreams and remind us that every night we let go of conscious control and slip into an irrational world of our own making.

Words by Rob Heath

___________________________________________________________###Matthew Herbert // Creative Director, New Radiophonic Workshop

Doctor Rockit, Transformer, Mumblin’ Jim, Wishmountain... Matthew Herbert has more aliases than you can shake a stick at. If you were to shake a stick at them though, Herbert would probably be there with a field recorder ready to sample the airy swooshing sounds and make a three hour concept album about it. It was a similar process he went through with 2013's The End Of Silence, where after being sent a five second recording of a bomb being dropped in Libya, Herbert set about using this to create an entire LP, raising issues about how we perceive war in the digital age.

One Pig similarly encouraged us to think about the farming industry after Herbert constructed an entire album using recordings on pig farms and abattoirs. Even earlier than this, Herbert's saw success was his Radio Boy project, in which he used all manner of sample sources to craft oddball sountracks to the dancefloor, kickdrums rattling like bones in a cardboard box. His 2000 album The Mechanics Of Destruction challenged rampant consumerism, given away for free and using samples of everyday disposable items - coke cans, newspapers, fag packets. The list goes on.

I remember a few years ago being excited for an upcoming Boiler Room appearance he had. Would he be spinning the blissed-out house of his Herbert alias? Or maybe a live performance from one of his pop endeavours? Instead we were treated to an hour of Herbert exploring the British Library’s sound archives, discussing some of his favourite sound sources and processing methods. Given the bewilderingly detailed, almost encyclopaedic knowledge displayed in this, it seems fitting Herbert was appointed as Creative Director of the New Radiophonic Workshop in 2012, an Arts Council funded venture to revive the institution. It might not be quite as expansive a reopening as one would hope for, but I guess given the current political climate, that’s to be expected, and I can think of no one better to have at its helm.

Words by Theo Darton-Moore

- Published

- Apr 15, 2016

- Credits

- Words by Stray Landings