1937 - 2016 // Don Buchla's Legacy

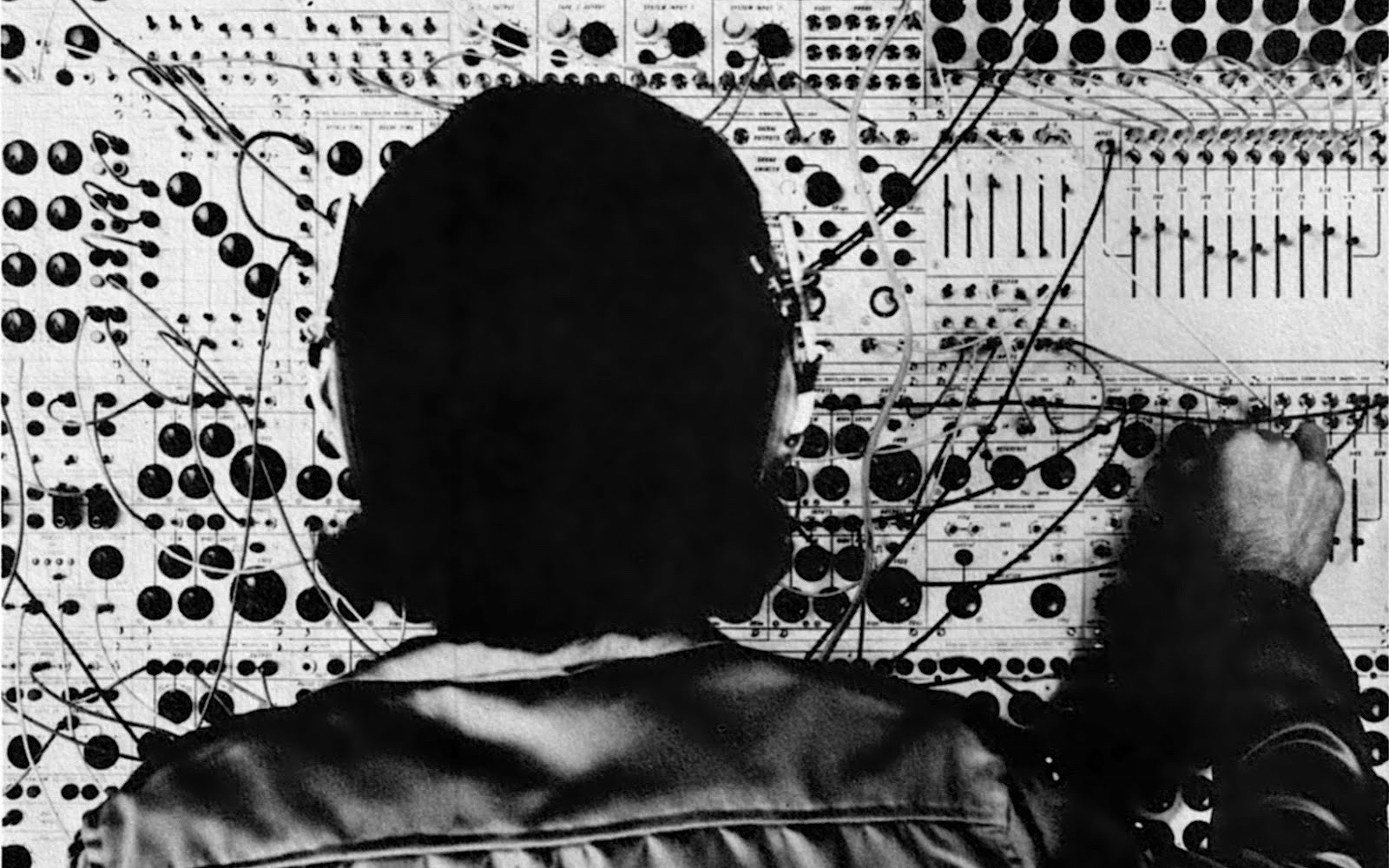

It would be hard to give any extensive history of electronic music without making some recourse to Don Buchla. A pioneering engineer, Buchla shaped the sonic world that we currently live in. In particular, the Buchla 100 and 200 series came to define a generation of synthesisers. These were among the first synthesisers to be built and unlike Moog, they came without any standard black-and-white piano keys. This set the Buchla series apart from any other instruments made hitherto. They were synths made as they ought to be: ultra-modern, experimental and alien.

Buchla’s notoriety first became apparent with the release of Silver Apples of the Moon, the first piece of electronic music ever commissioned by a record label. Written by Morton Subotnick on the Buchla 100 in 1967, its influence is truly immeasurable. But to simply canonise Silver Apples as just a curious historical artefact would be a mistake. Listening today is still as trippy as it must have been 50 years ago. There is almost no repetition and no discernible structure. The harmonics are peculiar and the rhythms are uncanny. It simply presents the listener with a set of expressionist forms, there to be freely interpreted. Funny to think that The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, released in the same year, is still regarded as ahead of its time. The work of Buchla and Subotnick outstretch the so-called radicalism of 60’s rock by decades.

Laurie Spiegel once wrote that when she first heard the Buchla, “Music went from black-and-white to colour.” At the time, Spiegel was living in the heart of avant-garde 60’s New York. This was the era of Steve Reich, Pauline Oliveros and Terry Riley; of minimalism, modernism and movement. “You were making the sounds yourself,” Spiegel continues, “as opposed to writing them down on a score and then hoping you could persuade a conductor and an orchestra to turn them into sound. You could immediately hear the realisation of your ideas.” This is the very essence of Buchla’s revolution. Much like early computers, synthesisers held a price-tag affordable only to rich bohemians and universities. But the Buchla required no classical training and no ensemble. An entire universe of sound could be made with one instrument and one player — an innovation unmatched by any instrument since the piano.

It’s no secret that gender has often been a barrier to music resources. Even as Director of the San Francisco Tape Music Centre during the 60’s, Pauline Oliveros remembers having to return at night to the abandoned studio in order to freely experiment. During this time, the composer and improvisor (now well known as the founder of Deep Listening) produced two of the most impressive pieces on the original Buchla Box 100 in partner with her tape delay system. Outside the window of her studio, she could hear the loud croaks of frogs in the pond and as she started to play, these sounds organically came to materialise in her work. These Buchla-born creatures swirl around her space-age sound world and get interrupted by the gentle voices looping off the tape machine, gradually building into an aggressive echo. These extended pieces (28/33mins) act as a reminder that electronic music can fall neatly into the human realm: they represent the natural way many Buchla artists work with their instrument.

The immediacy and intuitive nature of the touch sensitive Buchla were also the elements that first intrigued the classically trained composer, Suzanne Ciani. Working a day job in Don Buchla’s workshop and a regular face at the San Francisco Tape Center, Ciani is largely responsible for bringing the sounds of modular synths in general to popular culture. The 80’s were packed with her video game and advertising campaign sound designs, like the notorious sound of the Coca Cola bottle being opened and poured. For Ciani, the Buchla was an instrument like no other. She often left it running for months at a time to compose sounds and predicted that households of the future would each have their own Buchla.

Buchla synthesisers have made an unexpected return from Italian musician, Alessandro Cortini. Any good introduction to Cortini starts by sitting down and playing the entirety of his Forse Trilogy. An epic series that marks the producer’s shift away from his industrial rock band, Nine Inch Nails, towards a piece made (almost) entirely on the Buchla Music Easel. The trilogy allowed him to study changes in the sound of each note, through filters and oscillators, and how the dense textures could create a compelling track without traditional melody or tonal harmonies. Cortini’s work shows how deceptive the small keyboard of the Easel is. Each approach to the Buchla is one of experimentation and intrigue, one which can’t be laden with anything preconceived.

This year, Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith reappropriated Buchla synthesis for a new purpose. Beginning her career as a folk-musician, Smith swiftly abandoned the genre when introduced to the Buchla by a neighbour, becoming “distracted and enamoured with the process of making sounds”. This year, she released EARS, an album carrying the Buchla out of the stuffy indoors and into the outside world. Here, the Buchla is reinvented yet again, as an instrument of natural and organic beauty. Using granular synthesis, Smith distills her voice into woodwind tones and soft vocoder. The result is a lush and meditative record, miles away from the steely environment of Subotnick’s studio. Such is the elasticity of Buchla’s inventions.

- Published

- Sep 17, 2016

- Credits

- Words by jo_and_george