Echo Spaces // Julius Eastman

In 1975, the University of Buffalo hosted a performance of John Cage’s ‘Song Books’, a collection of Cage’s experiments in musical notation, facilitated by Morton Feldman and with Cage present in the audience. These ‘songs’ are notated in wild experimental style, from standard notation to Cage’s special brand of dots and lines to merely text highlighted in different sizes and fonts. Some of these pieces with more abstract notation give only a simple instruction, like "perform a disciplined action" or “give a lecture”. One performer, Julius Eastman, performed Cage’s instruction to give a lecture, inviting a young man on stage to undress him and make sexual gestures. Cage was furious with the performance, explaining that the instructions are not intended to allow the performer to “do whatever you want”, adding that Eastman's "[ego]... is closed in on homosexuality. And we know this because he has no other ideas."

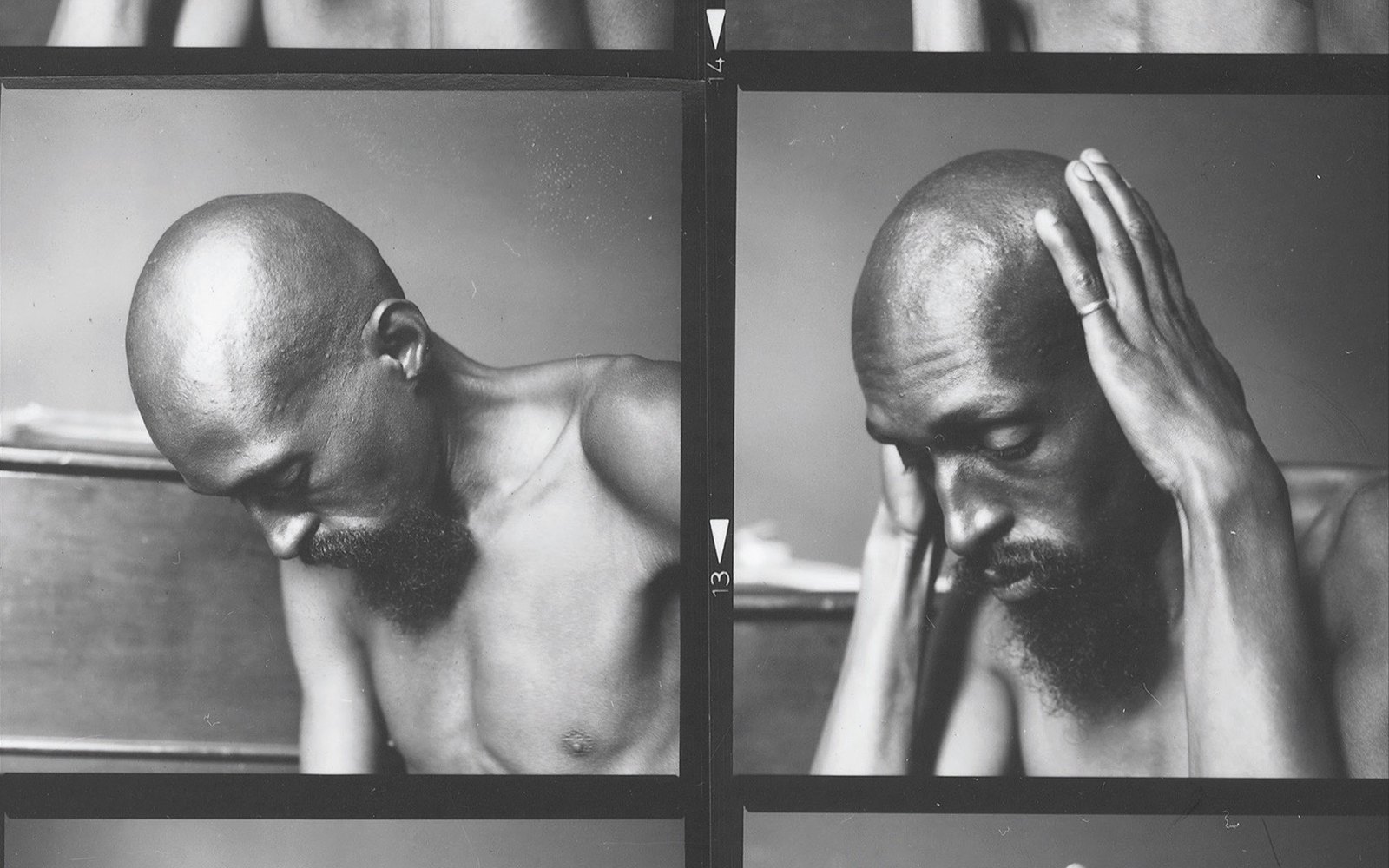

Cage was both right and wrong. It’s true that Eastman’s sexuality was central to his work. In the late 70s, New York’s burgeoning gay scene became a welcome home to Eastman (well, before he was evicted for falling behind on rent). In the Lower East Side, Eastman made historic connections, becoming the first male vocalist in Meredith Monk’s ensemble and conducting the orchestras for Arthur Russell’s instrumentals. In this sense, Eastman had a unique experience in that he came from both the academic minimalism of upstate New York, and the swinging hedonism of downtown Manhattan. But what Cage failed to see was the sprawling, searching mind of Eastman. His music is ‘out-there’, even for modern ears. And he takes minimalist ideas further, and into more dangerous territory, than Cage, Glass and Reich were willing to go. Even in his rendition of Cage’s songbook, Eastman attempted to disrupt the perceived acceptability of so-called avant-garde experimentalism, holding the radical aims of the project to its word.

Yet, Eastman died homeless in 1990 with little of his music remembered or celebrated. Even his obituary did not appear until eight months after his death. There have since been many attempts to revive an interest in Eastman, led by hardcore fans and the people who knew him. One such attempt at a revival is happening at this year’s CTM festival, which opens with a memorial dinner to Eastman and restaging two pieces for piano (‘Gay Guerilla’ and ‘Evil Nigger’) in new arrangements, interspersed with short theatrical vignettes on Eastman’s life and music. In anticipation of this performance, we look back at Eastman’s musical back catalogue and discuss three of his most important works.

###Femenine (1974)

Very little material of Eastman's still survives. There are almost no recorded performances and almost all of his scores were swept into the trash when he was made homeless. This adds to his mystique as a tragic and unknowable hero. But part of the recent resurgence of interest in Eastman is down to a re-release of Femenine on Finald’s ‘Frozen Reeds’ imprint last year. This recording was special in that it was one of the few high-fidelity recordings that remain of Eastman’s own performances. Here, you can listen to the unusual form of conducting that Eastman employed. The piece opens with a mechanical device designed to shake sleigh bells, a move now regarded as a jibe at the mechanical nature of Glass & Reich (a music devoid of the groove and feel of jazz). You can even hear the audience laugh as it is switched on. Each performer also uses a digital clock as a temporal guide to piece. The accompanying score instructed performers to modulate their playing at certain minute-marks. Although seemingly mechanical in its approach, the performance is anything but. Eastman even said of it that, “the end sounds like the angels opening up heaven”. But despite this spiritualism, Eastman’s sense of humour is never far away. In this 1974 performance, Eastman insisted on serving soup to audience members.

###Evil Nigger (1979)

Eastman experienced a lot of unease from his audience for the use of the n-word in his ‘Nigger Series’ titles: Nigger Faggot, Crazy Nigger and Evil Nigger. He remarked on this that “the reason I use that word is that for me, it has a basicness about it [...] the first niggers were of course ‘field niggers’, and upon that is the basis of the American economic system. Without field niggers, you would not have such a great and grand economy [...] so a nigger for me is that kind of thing which pertains himself or herself to the ground of anything.” The ‘basicness’ of Eastman’s music is felt in a piece like Evil Nigger, arguably his most emotionally raw composition. In a popular 1979 recording, the trills of piano are punctuated by Eastman’s own voice, shouting ‘one, two, three, four!’ to conduct a brooding refrain that sounds more like the dramatic climax of a Baroque requiem, music that Eastman learned and loved. But where the narrative arc of Western classical music follows the structure of crisis & resolution, Evil Nigger is all crisis.

###Gay Guerilla (1980)

One of Eastman’s most famous inversions of the minimalist tradition came through what he termed ‘the organic principle’ of performance. This is a cumulative technique in which new sections overlap with preceding motifs to create a dense lattice of musical expression. He once described the method, explaining (somewhat unhelpfully) that, “the information is taken out at a gradual and logical rate”. At points, it sounds like musical contradiction: a rhizomatic hodge-podge of paradoxical melodies. In ‘Gay Guerilla’, the pianos rise like Shepard tones into an ecstatic fanfare. At its peak, the piece merges into a cacophonous canon of the Lutherean hymn, ‘A Mighty Fortress Is Our God’. It has since been dubbed a 'manifesto’ for its ecclesiastical grandour and emotional power. In language typical to the ambiguity of Eastman’s thought, he once said of its title, “without blood there is no cause. I use 'Gay Guerrilla' in hopes that I might be one, if called up to be one."

Catch a performance of ‘Evil Nigger’ and ‘Gay Guerrilla’ as part of the opening concert for this year’s CTM festival. Tickets can be bought here.

- Published

- Jan 25, 2018

- Credits

- Words by Georgie_McVicar