The Great Outdoors // Art & Nature from Cézanne to Psytrance

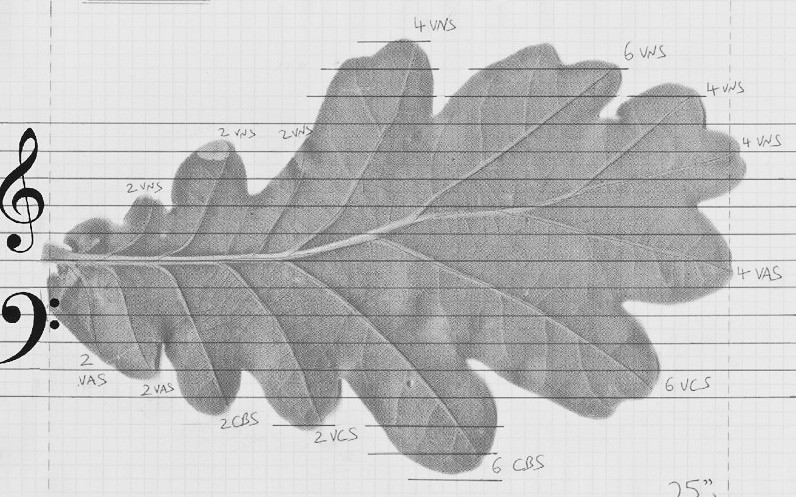

Part of the score for Jonny Greenwood's '48 Responses to Polymorphia', an homage to Krzysztof Penderecki.

After the Industrial Revolution, a lot of art portrayed nature in a pre-capitalist nostalgia. The Impressionists in particular presented life before the impending invasion of technology, progress, and modernism. They wanted to show a world that was neither hostile or in much need of change. One that was wholly-harmonious with humanity. Such a task may seem impossible. Indeed, many of the Impressionists became frustrated that their art could not capture nature’s infinite intricacy. A mere human could not pluck out the heart of its mystery. In a letter to his son a few weeks before his death, Paul Cézanne expressed his dissatisfaction after a lifetime of painting the great outdoors:

“...as a painter I am becoming more clear-sighted before nature, but […] with me the realisation of my senses is always painful. I cannot attain the intensity that is unfolded before my senses. I have not the magnificent richness of colouring that animates nature. Here on the bank of the river the motifs multiply, the same subject seen from a different angle offers subject for study of the most powerful interest and so varied that I think I could occupy myself for months without changing place…”

From Vivaldi’s Four Seasons to Prokofiev’s Peter & The Wolf and Debussy’s La Mer, classical music has made many attempts to regurgitate nature in musical form. But I have always found these impressions somewhat unconvincing. When they do work, the resemblances are cartoonish: like the quack of a duck played an oboe. Other times, the imitation has to be spelt out. If it was not called La Mer, would we still compare the string-swells to crashing waves? It’s almost as if the composer worried that his impersonation lacked conviction. That only by name would the likeness reveal itself.

To suggest that nature is infinite is also to suggest it is paradise. But a lot of contemporary music has rejected this notion. In the 1950s, John Cage began dissolving the historical opposition between art and life; mind and matter. Through a series of experiments, Cage made music incorporating silence, chance, and noise to show life’s brutal reality, not just its naïve innocence. In so doing, he didn’t only present new music, but a new way of listening. It encouraged an opening of oneself to the environment; to the ever-present here-and-now. It suggested the daring possibility that all noise could be music; and that all music was simply noise. Cage taught us that it is not enough to sound like nature, we have to be like nature too. For Cage, it was dishonest to represent the environment in part only. The natural world is a simultaneous muddle, and ought to be heard in all of its messy complexity.

Brian Eno made a similar ‘return to the natural’, writing music that not only evoked landscapes, but acted like a landscape itself. The birth of the term ‘ambient’ came with the release of Eno’s ‘ambient series’, starting with the landmark Music for Airports. The idea, as Eno recalls, came from spending time bedridden in hospital, listening to an LP of harp music:

“...I realised that the amplifier was set at an extremely low level, and that one channel of the stereo had failed completely. Since I hadn’t the energy to get up and improve matters, the record played on almost inaudibly. This presented what was for me a new way of hearing music – as part of the ambience of the environment just as the colour of the light and sound of the rain were parts of the ambience...”

Those early LPs in Eno’s ambient series (alongside Harold Budd and Laraaji) became genre-ative for a new music obsessed with scenery. Ambient is now arguably the genre most associated with nature, taking natural environments as its primary subject matter. Wolfgang Voigt has cited his outdoor experiences with hallucinogens as the inspiration for his ‘Gas’ project, working to, “bring the forest to the disco, or vice-versa”. Boards of Canada take their name from the National Film Board of Canada, whose nature documentaries provided inspiration (and sample material) for their work. Ambient even spawned environment-specific subgenres, such as arctic ambient, where the likes of Biosphere, Thomas Köner, and Marsen Jules replicate the glacial movement of ice and wind.

Field recordings have radicalised some of these principles. Taking the natural sound-world of a particular environment (rainforests, deserts, mountains), field recordings are made to leave you with nature ‘in itself’. Each represents an auditory document of a surrounding, a sonic snapshot from somewhere else. In so doing, field recordings attempt to expunge the human from the creative process altogether. Circumventing the observer’s paradox, field recordings offer a ‘view from nowhere’. As David Igantow once put it, “I should be content to look at a mountain for what it is and not as a comment on my life.”

Another purpose of field recordings has been to raise awareness of conservation. BirdNote in particular archives the sounds of birdsong from around the world, including those that are now extinct. Their goal is a kind of escapism, “transport[ing] listeners out of the daily grind and into the natural world”. In doing so, they hope to inspire listeners to deepen our care for nature, and ‘biodiversify’ our sonic environment. The ecology and art platform, Worm, have warned that such an approach risks romanticising extinction. The field of acoustic ecology makes a similar move, logging the diachronic changes of an environment through sound. One famous example of acoustic ecology tracks the buzz of insects in response to increased pollution levels. Through deep listening, and analysis of sound, we can track changes that remain hidden to the eye.

The ‘90s brought an unusual resurgence of the environmental movement. Mystic ravers Spiral Tribe espoused an anarcho-primitivist politics, hosting free raves (or ‘gatherings’) in the open spaces of the home counties. Their calling was to make a primordial return to our prehistoric selves through dance. In many ways the UK rave scene wished to hit reset on culture, to free us from the tyranny of history, and start again decoupled from capitalist drives. Psytrance also flourished, marrying spiritual mantras with animal song. It even produced a subgenre, ‘Forest’, devoted to organic and earthy timbres. At the time, new age spiritualism had entered the public mainstream. First Lady Nancy Reagan visited an astrologer, Princess Diana consulted spirit mediums, and Norwegian Princess Märtha Louise even founded a school dedicated to communicating with angels. There was also a resurgence in UFO conspiracies, healing crystals, and spiritual self-help manuals. One unintended consequence of this was the introduction of ‘chillout’ CDs. British supermarkets sold whale-song, rainfall, and dolphin sonar for the ‘stress-buster market’, fortifying the urban info-warrior for battle. A spring-cleaning of the head for a clearer mind in the office.

I suppose there is something strange that music based in electronics wants to replicate nature. After all, there is some squabbling amongst musicians over the perceived ‘naturalism’ of certain electronic sounds. At some point in the past, detractors regarded almost all electronic music as lifeless, cold, animatronic. This is perhaps unsurprising given its pre-occupation with futurism, cyborgs, computation and so on. But now, hardcore tech-heads have begun arguing for the ‘warmth of analogue’ as a justification for its superiority. John Peel once defended the pops and hiss on vinyls by retorting, ‘life has surface noise!’ But why would we want our music to sound like life in the first place?

There is no reason to assume that nature has an inherent beauty or benevolence. Such an assumption is what philosophers call ‘the naturalistic fallacy’. Talk of this or that behaviour being ‘natural’ and thus desirable makes a false equivalence between what ‘is’ the case and what ‘ought’ to be the case. This can lead to some dodgy politics. So-called ‘race realism’ and ‘scientific racism’ used measurements of the natural world (skull size, phenotypes, genotypes) to justify pseudoscientific compartmentalisation of race into a hierarchical system. Today, the alt-right and white supremacists are renewing an unhealthy obsession with genetics, as can be seen in the recent uncovering of a secret eugenics conference held at University College London.

Talk of biology or ‘naturalism’ is also often brought up in the context of queerness and degeneracy. The Christian right often condemn gay people on a naturalistic basis, citing reproductive organs as a kind of sexual instruction manual, a heterosexual imperative: have babies, or else! Trans and non-binary people are also under scrutiny for ‘deviating' from nature. Anti-trans rhetoric almost always comes back to talk of biology in an essentialist attempt to legitimise and justify transphobic violence. This same logic is also used to invalidate gender nonconformity and non-binary identities, such as in the reductio ad absurdum attack helicopter meme. Homophobes once argued that being gay is a slippery slope to beastiality; transphobes now argue that being trans is a slippery slope to identifying as helicopters.

Many queer artists have thus had a rocky relationship with mother nature. But some have reclaimed this focus on biology, with a clever twist. Looking back to the body can open questions around the anguish of gender dysphoria, or the experimentalism of queer sexuality. Arca and Lotic refocus on the body in their artwork, where we see contorted skeletons and bulbous fleshy torsos. In Sophie’s latest video, her face is stretched and manipulated beyond recognition. AJA also recently donned a ‘femme guts’ costume on stage: external intestines made of bright pink sequins.

For me, the most rewarding art depicts nature as an unpredictable disunity. Think of the chaotic spontaneity of Olivier Messiaen’s avant-garde birdsong, or the wild oscillations of Merzbow’s Dolphin Sonar. In De Natura Sonoris, Krzysztof Penderecki's scratchy string pieces emulate nature's scary side, like the brittle sprawl of dead tree branches. Orla Wren has made sonic representations of the birds and the bees, but included with them the (often unpleasant) squarks and screeches of wildlife. Animal Collective sample the squelch of insects in mud; they growl and yelp like possessed children.

Too often, artists cherry-pick the sweetest fruits of the outside world. We sing of raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens. Like Cézanne before, this shows the world not as it is, but as we wish it to be: elegant, beautiful, cohesive. Eden before the Fall. Seldom do we see the tooth-and-nail struggle for survival that is integral to the natural world. If art has any purpose, it is to reconcile us with our difficult world. But such a reconciliation must first offer a vision of nature that is all-encompassing: all the way from the petals of the flowers down to the rotten undergrowth.

Listen to our latest Resonance FM show on music and nature with Moonbow and Worm here.

- Published

- May 7, 2018

- Credits

- Words by Georgie_McVicar