Mean Grey Value // Christoph de Babalon

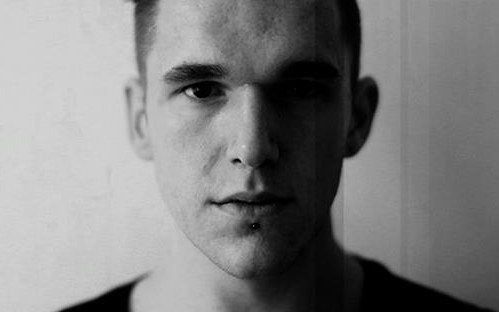

It's hard to paint an accurate picture of Christoph de Babalon. Not least because almost all of his press photos are shot in grainy black & white. The late John Peel placed one of de Babalon's earliest releases, I Own Death EP, in his 1994 end-of-year list. Two years later, de Babalon was taken under the wing of Digital Hardcore Recordings (DHR), a fringe label that specialised in some of the harshest and most abrasive contributions to music in recent memory. It was here that he first caught wider public attention.

His debut on the label, If You’re Into It, I’m Out Of It is something of an unsung classic. The album's high contrast artwork and ironic title capture of the mood of the time. On the one hand, it is cold and maths-y, like the Neo-Noir psychologism of Aronofsky’s Pi or Lynch’s Eraserhead. But it is also carries a certain swagger, an adolescent anti-everything nihilism. Thom Yorke even described the record as “the most menacing album I own”. de Babalon also consequently went on to support Radiohead on their 2001 Amnesiac tour.

At this point, club music had reached an interesting juncture. The optimism of early rave had given way to a darker outlook. The smiley face of acid had morphed into a evil grin, and the melodic riffs and vocal hooks became displaced by yet more percussion and digital processing. This turn to the darkside produced some of electronic music’s most striking and heavy contributions. DHR were instrumental here, incorporating almost all aspects of ‘extreme’ music (punk, gabber, noise) into one glorious monstrosity. These releases have a bleak trajectory to them, as if written to accelerate the deterioration of social fabric. Take Atari Teenage Riot’s anarchic manifesto: Burn, Berlin, Burn, also released in 1997. This was music from the tail-end of Generation X: bitter and violent, its aims were the abolition of all culture and the creation of none. A self-destructive rush into a hot furnace of overdrive.

It’s often said that while most genres develop as hybrids of two or more styles, jungle is more like a mutant. Tech-house or dub-techno are clear in their lineage, a cherry-picked composite of two distinct styles. But jungle, born out of techno and hip-hop and yet nothing like either of them, is a different beast. In 1992, Derrick May warned of this impending new genre as, “a diabolical mutation, a Frankenstein’s monster that’s out of control”.

If jungle is a mutant, then Christoph de Babalon’s music is a mutant’s mutant. If You’re Into It, I’m Out of It is both hardcore and ambient at the same time, a combo Philip Sherburne described as “a hellishly compelling couple”. Just listen to the epic 15-minute opener, ‘Opium’, a track that predates the gothic ambience of artists like Demdike Stare. In fact, I dare say that DS directly lifted its chords, style and sound for their 2010 track, ‘Matilda’s Dream’…! But then there are explosive breakbeat experiments, like ‘Water’ and ‘My Confession’ that lash out like rabid Rottweilers. Too weird for a rave but too rave-y for the home, If You’re Into It, I’m Out of It exists in a netherworld that is still not understood.

But to talk of Christoph de Babalon only in terms of his earliest work would be a mistake. Over a career spanning two decades, he has pursued styles from cinematic soundscapes to bitfucked breakcore, and the conceptual depth of his work requires considerable time and attention. Scylla & Charybdis, for example, is a stunning, operatic record that de Babalon worked on for three years. The album uses styles influenced by Schönberg, Rachmaninoff and Strauss. His latest album Short Eternities pays tribute to both his jungle origins and his fondness for the abstract. There are moments of hyperactive excess, but always with a stirring malaise lurking underneath. In celebration of de Babalon’s return, we caught up with him to talk juke, Tarkovsky and pessimism…

Your very first record came out over 20 years ago now, how have you seen your attitudes towards music change, and how has culture responded to it since you first started playing?

I don't know. I can still be pretty enthusiastic about music; listening to it and making it and so on. But I guess, I am less easy to impress these days. Musically, I am mostly exploring the past. I don't really feel like I need to be up to date, if there is such a thing. Generally, I have been trying to make as much music as possible while staying as far away from the music scene as I possibly can. Or people in general... I like to be on my musical island. Something interesting will always wash ashore!

Seven years ago you released Scylla & Charybdis, a concept album that at the time you described as the “most complex work [you] have ever done”. What, if any, are the conceptual markers on your new record? What should we listen out for?

I am happy with the monumental concept of Scylla & Charybdis but doing this all the time would have been annoying to everyone. Short Eternities is just a number of tracks that work well together. I did not feel the pressure to re-invent myself. But I do think this record has it's very own poetic feel, which I have yet to put a name on. In parts there are pretty aggressive breakbeats, but mixed with the ambient tracks the albums gets a real sense of fragility.

I’ve really enjoyed your work in ambient in the past, and I’ve felt like jungle and ambient have an unexplored crossover outside of your music. What are your aims when trying to bridge the gap between the two genres?

I guess my idea is very simple. The mood is kind of similar, at least the general direction, in almost all my music. Some works just happen to have no beats, or not much of a rhythmic pattern. But they all want to drag you in, so to speak. Luckily, the fact that I do 'ambient' AND jungle is my slightly schizophrenic trademark.

I’ve read that you’re more interested in creating atmospheres in your music than anything else. “Music that really creates a world around you and in you” as you put it, and you cite inspiration from classical music, literature and the visual arts. Could you name some examples of things outside of music that have made a big impact on your work?

Earlier it was visual stuff like Arnold Böcklin, Gustav Doré, and I always liked Bosch and Bruegel with their intense atmospheres. In terms of books I would have to say Burroughs and Robert Anton Wilson. Oh, my!

…and film too?

Yes, very much sometimes, especially films by Kubrick and Tarkovsky, but just as much as anything else. Like life in general.

A lot of your tracks stretch out to incredible lengths, I’m thinking in particular of the nearly 16-minute epic, ‘Opium’ that opens If You’re Into It, I’m Out Of It. Seems to be quite a rare format for someone working in your genre.

I agree, the choice to put 'Opium' as the first track was a brave decision made by the label DHR at the time. Probably, back then, I would not have dared to make that choice. So it was great, someone more reflected took care of it.

Would you say this is in some sense a reaction to the commercial nature of fast-paced music consumption today?

I guess, people want to listen to it because they can relate to the mood and they are looking for in these atmospheres. I will not be able to catch a fast paced person’s attention with my autistic musical project for very long anyway.

Could you maybe say a few words on where you see the future of Drum & Bass? There was a time when D&B and Juke seemed to making some kind of fusion, but I notice that you haven’t jumped on that bandwagon. Will the genre remain a relic, or is there still a resurgence waiting to happen?

Juke is fun, but I have no idea what is going on in Drum & Bass these days. I am sure it will be around for a while, and that's totally fine with me. However, for some strange reason I never really felt part of Drum & Bass. It did have a big influence on my work, especially the stuff from around ’94, when it was fresh and silly and producers weren't trying to 'make music'. But people got too anal about the whole production thing and the music lost its charm. I do not expect an established musical genre to re-invent itself; that would be confusing.

Finally, a lot of your work seems to hone in on the dark elements of life, and uses an extremely gritty sets of sounds to achieve some truly melancholic affects. You even once described life as “tragic and utmost brutal”. Would you call yourself a pessimist?

I really try to be positive, because being pessimistic is sometimes an easy excuse for not doing anything. But then I open the newspaper... and it seems the world is made of pain and sadness for most people. It is hard to be positive but it’s the only way.

Short Eternities is out now on Love Love Records.

- Published

- Nov 17, 2015

- Credits

- Words by Georgie_McVicar