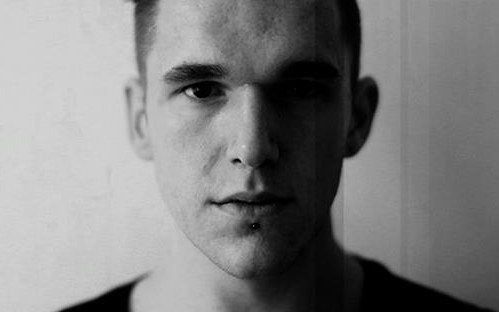

Focal Point // Rupert Clervaux

“The inspiration of Leopardi resonated for me around the idea that you have your finished work and then your process, your backdrop [...] your research - and all of his research is available, it’s free to view. And 'Zibaldone' in a way was me saying, well, mine’s also free to view if you care to view it”

Rupert Clervaux’s new ongoing series takes its name from the notebooks of nineteenth century poet Giacomo Leopardi – these Zibaldone, the original Zibaldone, were a comprehensive collection of notes; personal impressions, ideas, observations, sketches for later, more developed work - published posthumously and just recently translated.

“It was this idea that there was the sense of the real life of a poet or an artist from a long time ago, from another place - and this perspective you get from having the focal point of the poems themselves against this incredible landscape behind it; the Zibaldone. And that’s what I found so appealing.”

It’s certainly a function of his own Zibaldone, which operates as a series of audio notebooks in which threads of sound, rhythm and spoken word are joyfully interwoven. Each release veers wildly between disparate pockets on an enormous map of musical hues; ambient glows, stabs of free jazz, lolloping anarchic loops, chatty, frenetic percussion exercises. The tone roams with the genres - in parts achingly sincere and then with a curt left turn mischievous or crude.

“I wanted it to be like an audio notebook. So it’s not me saying; ‘this is my preened and stylised output that I’ve really thought about.’ It’s what could potentially become that later - but maybe there’s some value in seeing that process exposed, or arresting it before I think too much about how it fits into a specific vision of how it should or would sound ideally. I got that impression when I read [Leopardi’s] notebooks for the first time… that in his poetry you get a very different sense of the person... In the poems he feels open minded but very much affected by his ailments, and by his pessimistic tendencies. And the notebooks don’t seem to have this for me at all. They feel totally open, you know - sceptical and cynical in the old fashioned sense where you question all points of view rather than focusing on one and seeking to promote it. And I just wanted it to be like that. There’s no one style of music I’m trying to be part of or promote or... it’s just a relay of ideas”

In each release we witness Clervaux playfully hold up and examine the rhythms, timbres, artists and ideas he adores. The project allows him to return to and explore his own fragments which may have otherwise lain discarded on the cutting-room floor, whilst simultaneously paying homage to the thinkers and poets he holds so dear.

Part one opens with a soaring, cinematic discourse between wide, austere synth swathes and the melancholic chiming of a delay-treated piano. Over this, Imitatzione, a Leopardi poem, is recited by Mara Cimatoribus, setting the theme. The synths swell to envelop everything, apart from restless, partially obscured percussive rolls. These rattle around just out of sight before sweeping smartly on to centre stage and into their own brusque dialogue. The pace of the project unfurls as this; the continuous flowing juxtapositions piece together a colourful collage, creating new shades and angles from repurposed material held in tandem or parallel, revealing Clervaux through his collected statements – that is, the words and work of himself and others. It’s a project which, whilst simple and visceral in its drive, is as complex as any relationship between a person and their passion. Clervaux explains to me that his relationship to music has been subject to modulation in recent years – its perceived function in his sphere, the time and headspace he dedicates to it, how it moves him and how he utilises it.

“For years when I was younger I used to have an infinite appetite for intellectualising about music, but for some reason it started to wane... the more I became obsessed with reading, the less energy I had for intellectualising about music. And I’ve never really been a music collector, a record collector, so I’m a bit out of my depth talking about what year a record comes from or this type of thing. And it just suddenly made sense to me that I had a primarily physical connection with music. Playing drums, listening to rhythmical music - that has an effect on me physically, and that’s what draws me to music. And what draws me to literature is a more intellectual mindset and I wanted to find my own crossover, a different crossover to the one that I was used to. And I think that in a way, what I’m doing now represents finding a different place for them to intersect […] So, for better or worse, what I’m doing now, it’s just finding an intersection that makes sense for me. Thank god, at last, it really does, you know…”

It is with the energy that he may have once enthused about the conceptual conceits of music that he now dedicates to articulating his own poetic thought.

“Whereas music I can come in and out of, I feel very laid back about it. I get very frustrated if I don’t get time to write.”

Clervaux has clearly a very pure and intimate love with literature. He references confidently and widely, quoting TS Eliot, Geoffrey Hill, Gottfried Benn, and Thylias Moss among others during our conversation. His mix for Mitamine Lab contains snippets of him reading from Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet. He’s also currently working on an LP of his own poetry and music which should hopefully see a release around the beginning of next year.

This love for writing he is now able to express with the Zibaldone. It marries two parts of an artistic psychology, instinct and intellect. He suggests the project could also act as a sort of reading pattern, marking a timeline by collecting the thinkers and artists who’ve meandered in and out of his thoughts, leaving an impression. The position that writing now serves allows music to occupy a larger, freer, more honest space in his worldview. And so the Zibaldone functions as a channel for Clervaux to harness and express the physical and intellectual sides of his artistic persona, in a way he feels comfortable and excited about doing.

“I’ve spent years of my life talking to people about music and enthusing about music I like, and ripping music I don’t like to shreds for whatever reason, you know [laughs]. And I started to lose my energy for that. What then came out of this musical fallow period was that whatever intellectual headspace I have, I wanted to fill it with poetry, philosophy, history, politics… I didn’t want to put music in that space any more. And I thought there might be a more exciting way for me to combine my literary interests with a physical drive to make and perform music. One of the funny things that came out of that fallow period for me was just thinking about dancefloors again, you know... and I started dancing again, which I hadn’t done for years. I suddenly became obsessed with dancing again.”

The fallow period he hints at came about after dissolution of a long-term project:

“Looking back, I was just struggling against a democratic way of making music. It was almost a joke then that I had a tendency to be a control freak in the studio, and maybe after years the joke began to wear thin on all of us! It was a difficult time because we’re all old friends and I respected them a great deal as collaborators, and still do as musicians. But when it ended we were all free to move in the directions we were pulling in. And what I wanted was not to think about creativity democratically […] I mean, for me, democracy is a political concept, it’s not... it doesn’t need to be applied to art. And I don’t think that art benefits from being democratised either.”

From this dissolution Clervaux found himself in a place where he wasn’t completely dissatisfied, but ultimately wasn’t pushing himself either. He continued his mastering work, his reading, his writing; he joined Hot Chip alums Al Doyle and Felix Martin in the band New Build sessioning as a drummer, touring and exploring this newly realised physical relationship to music with an excited fervour.

New Build

New Build

“I would look out at a room of people and there was this group elation, bodies dancing, and there was an undeniable physical excitement to playing drums right at the side of the stage [a stipulation when performing with New Build] and having people right there who were having a totally immediate response to it. And where I’d thought that was the type of thing that I wouldn’t like so much, I was amazed by how much I liked it. It genuinely changed the way I thought about performing music.”

The end of this fallow period he sees as owing to one person, his now long-time collaborator and close friend Beatrice Dillon. Meeting through John Coxon, head of the Treader label and half of Spring Heel Jack, Clervaux assisted Dillon with some mixing and mastering for a performance at the ICA. Following a collaboration at Cafe OTO they continued working together and have made some astonishing, considered records, which cleverly measure and plot weight over spatially vast or intricately detailed soundscapes.

“...at the same time as I was playing in New Build, Beatrice brought me into a few situations where she wanted to collaborate - and very generously really, because she was out there doing exactly what I wasn’t doing; hunting for and finding opportunities. And she would invite me to do them with her... these resulted in ‘Studies for Samplers and Percussion’, resulted in ‘Two Changes’ - so, she was an instrumental figure in pulling me back into a creative, musical mindset”

Remembering the writing process for their Studies for Samplers record he mentions how, “maybe the one rule that we said we had for that record was ‘when it stops being an idea we have to either throw it away or just stop working on it. Basically there’s zero production on that record.”

Each instalment of the series is bound under a governing chapter heading, or theme; the first imitation and originality, the next mental health, the third government and politics. Clervaux is quick to point out that the themes were organic byproducts themselves, coagulating almost of their own volition. As certain pieces came to their denouement, connecting strands began to bubble to the surface.

“At the beginning there were lots of individual pieces floating around, and I started to group them together. Then naturally for the first two [parts] some relatively loose themes seemed to be holding certain pieces together in their own gravity. The first one had this very poetic approach, and I wanted there to be a Leopardi reading. I was thinking about originality in music, because probably for the first time ever I was getting involved with cutting up other people’s music, and so there’s this Leopardi poem, 'Imitazione', which felt appropriate. At the time I was reading Silvina Ocampo, a phenomenally good poet, and she had a poem of the same name and, suddenly it was all there... These five bits that existed just needed a final topcoat, and that was done. And I noticed that of the remaining pieces that existed there was a vague psychological theme to some of them. And that’s where ‘I on Crack’ fit in, and so I put those together and... it’s horribly disparate part two, in the way it goes from one track to the next [...] I feel more fondly about two than one in that respect because I think it’s more... brutal.”

The themes are fertile ground for speculation, the use of sampling, drum loops, lifted lines of poetry, and fragments of his own work (the same otherworldly shimmers of the bowed vibraphone which appears in “A Different River Once” are heard at the end of part one) could suggest much about Clervaux’s thoughts on imitation and the nature of originality. But instead of determining whether in essence the value of originality is given too much stock, or instead of making a point about the intrinsic nature of imitation in art, nature, or society, Clervaux collects ideas about the subject and arrange them as interesting nodes on a larger flowing stem. And so instead of some incredibly arch comment on originality in music in which samples are brutally xeroxed to a shadow of their recognition, he presents some beautiful pieces of music interspersed with poesy about the nature of imitation. Which, when collected together show us Clervaux is aware of these pieces, he can see the value in them, and he sees them as valuable enough to present to us.

“[TS Eliot’s] take is that all great art is historiographical and the only way you can be forward thinking is to accept that. There’s a sort of sham version of ‘forward thinking’ which says ‘I ignore the influence of others and what I do is truly original’ – and for some reason that type of sham thinking has been given a lot of currency. People want something that is a radical departure or a ground-breaking progression. That type of need has created this strange currency and kind of sham originality that likes to sweep its influences under the rug. And it was reading that essay [Tradition and the Individual Talent] that was another sort of influence for the birth of 'Zibaldone' [...] if we just talk about the concept of originality, I think what he’s saying has traction - which is that if you understand what’s gone before, you then have the opportunity to be original - but you do so wearing the debt on your sleeve. And that maybe originality doesn’t need to be this wow factor, it needs to be new ways of... interpretation. Of course, as time goes by we’re painting ourselves into a corner more and more if we need to have this wow factor – you’re either painted into a corner or the wow factor is not real... the choice is yours”

And it feeds into Part two, in which samples of Angie Stone’s “Wish I Didn’t Miss You” and the O’Jay’s “Backstabbers” are turned into an eight minute building loop which ducks in and out of the stereo field. In fact, on the Zibaldone II Bandcamp page, Clervaux explicitly explains the intention behind this section:

“...repetition changes tack again to reveal its hypnotic, abreactive side – excavating and closely examining a rich psychological seam in Angie Stone’s lyrical strata, as a fragment of her classic track relives its origins in the O’Jays ‘Backstabbers’...”

In this track, which he’s titled “Memories Don’t Live Like People Do”, Clervaux has made a transparent, triple-tiered connection between the two tracks, exclaiming his affection for both whilst also positioning it in a way to suit Zibaldone II’s needs. As each chapter unfurls itself, it’s not a preachy, didactic listen. Overwhelmingly it’s the raucous, swerving-yet-calculated adjustments in pace and tone and nuanced production which hold a firm grasp on the attention, and as the strewn allusions to the thematic banners are suggested it is merely for the listener to piece together if they wish, rather than a lesson in moralising from the artist.

“The themes bubble to the surface and occur naturally, from below, on the basis of what you’re interested in at the time. That’s a key element to how I feel comfortable working. I don’t feel comfortable working in a way where I say I’m interested in this and then fill in the gaps. I feel comfortable with a method which takes [an] interest and then works inquisitively. And you hope it’ll coagulate into something that makes thematic sense to someone who hasn’t been through that process, that they just receive it and think “OK, I can thread that together”... but it’s not a presumptuous thing. You hope someone will get it, and doing that you give them the freedom to thread it together however they like, and that’s fine”

The sentiment is similar to one articulated by Geoffrey Hill – an observation in fact made by his friend but held particular traction with Hill;

“[it is an issue] that somehow art is diminished when it’s overpowered by obsessive self-expression, and that somewhere along the line between ‘self-expression’ and ‘expression’ in its wider sense, is a sweet spot where it’s not someone just exposing, or imposing, their inner workings, their distress, their love... it’s something which is depersonalised to the extent that someone can just walk by it, or listen to it or read it and say ‘yes’ [clicks fingers] I get it, I understand…”

And so the dance performed by the Zibaldone is a confident, funny one; one which doesn’t prize the way it looks and is at the total mercy of the music moving it. One which inhales its influences and exhales its author.

“CVX represents a different side to me than - in the terminology we’ve been using with Leopardi – my stylised side. When I think about how I want to write a poem, or make a piece of music that’s expressive, it generally doesn’t have the sense of humour that I feel I have, as a person [...] As CVX, and in the 'Zibaldone' particularly, sense of humour has a natural role. And it’s all... and this is where the inspiration of Leopardi comes in - it’s all notes, it’s just notes. It’s not to be taken that seriously. They flow off the tongue, they just happen. And for the most part they represent pieces of music that would never have come seen the light otherwise. So in a way it was a decision to actually follow those whimsical thoughts that you have about a piece of music, or to retrieve that curious section that was discarded a few months ago - to do it and not to labour the point at all. Not to think about how it fits next to something else, and that’s it. Just like taking notes, like scribbling marginalia, but in a music studio instead of in a library...”

- Published

- Apr 23, 2017

- Credits

- Words by Elliot_Stevens