Reverse Engineer // Yair Elazar Glotman

It's hard not to be impressed by the musical background of composer Yair Elazar Glotman. With education in jazz, classical, then electronic music, his influences are vast and varied. Anyone who has listened to his music can hear this. There is of course the technical proficiency of the playing — the contrabass in particular. Each record also sounds live in the ‘here-and-now’; as if played before your very eyes at a jazz club. But he also brings a modern sheen along with electronic processing to elevate the pieces into the avant-garde; not as a cheesy add-on or afterthought, but through subtle layering and reduction.

On his latest record, Compound, Glotman brings all three of these features together. A trio of jazz musicians improvise motifs, loops and tonal ideas around Glotman’s instructions, later manipulated and contorted in the studio. The album has a creaking and uneasy sound to it, with a perpetual sense of incoming danger. This marks the second Subtext release for Glotman, and adds yet another to the label's impressive flurry of albums this year. In anticipation of this release, we caught up with Glotman to talk about the making of the record, the philosophy of improvisation, and regaining trust in other people.

I've just finished watching the new series of Twin Peaks, and it got me thinking about the the types of abstraction you can achieve with TV versus, say, music. People often say music is the most abstract art form. Do you agree?

Somehow David Lynch managed to create abstraction in visual language. TV and film almost always has some kind of reference to something, but Lynch managed to make something more atmospheric and 'free-form' with his work to tell his stories. For me, listening to music (say on headphones) is very different from seeing live music. I guess live music is the original form of music: the very earliest music was probably just people banging on stuff, and then music as an abstract idea came around the end of the 19th century with the development of recorded sound medium. Hearing a note on headphones is so abstracted away from the original instance of the note being played. When you watch someone play violin, you have this very clear sense of the cause and effect between the player and the sensation of the sound. But when you listen on headphones, you could very easily forget that this is art generated by human beings. It's almost like the music is being produced by your own head.

You've done a lot of work with film, how did you get into that?

I've always been making music for short films and video-art. I studied media-art so I was always studying generative art and sound-art. But I had a lot friends making experimental films so I was always collaborating with them. In general, I am Interested in the use of music and sound various mediums where its role changes.

I think your music lends itself very well to cinema. Especially with Compound, I have this ongoing film running through my head when I listen to it.

Right. When I write for other mediums — for example in my practice of sound installations — it's more about creating a kind of environment, rather than a strictly visual idea. That could be just an emotional environment, or atmospheric tension. So when I write for films, it’s just taking that environment and making it more precise; more visceral: you're hearing and seeing the environment at the same time.

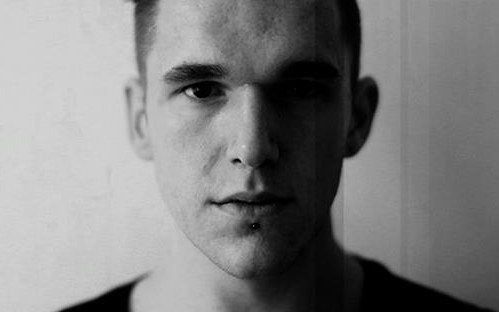

Photo by Camille Blake

Photo by Camille Blake

Can you tell us a little bit about your history with the contrabass?

I studied jazz before shifting to classical, when I was about 14 years old. Around 5 years ago, I left the contrabass for a while but I started to feel the big sensation of guilt for not playing it. It’s such a big piece of furniture, it’s hard to ignore. I began to feel haunted by it, so I had to return. But I also wanted to free myself from the instrument (its traditional playing style, typical sounds) and find a way for the instrument to play itself. I’m interested in trying to deliberately lose control of the instrument. So I started using feedback chaining within the contrabass. And that got me back into using the instrument.

I think it’s important to free oneself from an instruments traditional usage. One issue I have with singular instruments is that you usually have to be part of some group to create music. Laptops don’t have this problem — you can be everything at once.

Yeah but I haven’t forgotten the importance of collaboration. I used to be frustrated by being a bass player, and relying on other musicians to express myself. Like you say, electronic music is very freeing in that sense. But you can get completely lost in the do-it-yourself mentality. You start to get lost in your own ideas. So I’m starting to gain trust again in other people (laughs).

You had that release with Mats Erlandsson earlier this year, for example.

This is maybe the first example of a successful collaboration for me. That album was very inspiring; to find someone you share trust and sensibilities with. Not a lot of people know this but Mats is also an amazing guitar player. We were playing around and decided that we wanted to create fake medieval music. That was the starting point.

I was surprised to hear that there was a lot of post-processing on this record. It's sounds completely live to me.

Yeah there are many many layers of improvisation on this record. On a technical level it was like developing a system or language of improvisation. I would instruct these techniques and they would change and evolve depending on the improvisors’ comfort with a particular motif or their mood at that time. Compound is like reverse-engineered live music. I also had to think a lot about how to record and how to play to create these layers. Wanting it sound live and unlayered was totally the goal I was aiming for. There are times when there are six different takes on top of each other but they are completely hidden. You kind of deconstruct and rebuilt the whole thing.

It’s also a very spectral focused piece of music. Sometimes there would be 16 different microphones for one take, and after layering few takes I would end up with about 200 channels which turned my mixing process into a Sisyphean climb. My aim was to sounds like a trio with 12 pairs of hands (laughs).

I often see that as the kind of goal of a lot of electronic music — to reintroduce this ‘live’ or ‘physical’ feel, which is often lost with laptop performances.

Yeah that’s why I’m interested in this dissonance between improvisation (like capturing a certain moment) and post-production (where you closely analyse the materials and sounds). But you always have this backbone of energy from the original performance.

What have you got planned for the rest of the year?

I am brewing some ideas at the moment but nothing concrete. I need more time to develop something meaningful to me at this moment. At the moment, I feel as if I have reached a limit of what I feel I can do, what I feel inspired by in myself. I am looking for others to work with for inspiration right now: musicians, teachers, composers… I need a reset.

Compound is out on Subtext on 6th October.

- Published

- Sep 21, 2017

- Credits

- Words by Georgie_McVicar