486 Hertz // Ellen Arkbro

This year saw Berlin-imprint Subtext release a flurry of staggering full-length albums, beginning with Ellen Arkbro’s For Organ & Brass. At the time, Arkbro was known to some as one of the many young Swedes engaged in Stockholm’s bustling experimental electronic scene. Three foundational institutions (EMS, Fylkingen and the Royal College of Music) have produced a fertile ground out of which budding musicians can blossom. Caterina Barbieri, Yair Elazar Glotman, Mats Erlandsson, Maria W Horn, Daniel M Karlsson, Sissel Wincent, Kali Malone and many more all seem to have grown out of this environment. Consequently, we have the Drömfakulteten imprint, the ‘Stockholm Drone Society’ and the crown jewel of Stockholm electronic scene: Norbergfestival.

Brian Eno coined the term 'scenius' to describe moments like this, as “the intelligence and the intuition of a whole cultural scene [...] the communal form of the concept of the genius.” A uniquely modern trend in music, particularly from electronic music and DJ culture, trades the role of the lone 'tortured artist'- type pioneer for a collective hodgepodge of innovation: from 'gene' to 'scene'. In other words, Stockholm seems to have the enviable status of having an actual community. Perhaps if London gave similar attention to its arts funding, it wouldn’t feel so atomised by comparison.

Arkbro’s initial experiments on texture, tone and timbre can be found on Soundcloud, catalogued by their date of creation and nothing else. This is the world so many musicians start in: self-uploaded tidbits and experimental obscurities. Not much else on Arkbro was in the public domain before this year, so I guess I was kind of surprised to hear something like For Organ & Brass as a debut full length release. Because this is an ambitious, mammoth record. The kind of thing you release at the height of a career, instead of at its beginning.

At first pass, it’s easy to get distracted by the novel aspects of this album. The opening piece uses a 400-year-old organ, tuned to the subtle but seductive ‘meantone temperament’. This is a tuning rarely heard. It sounds kind of 'rounded out' and warped. In meantone, a chord on its own feels more spherical than usual: a tensionless harmony of frequencies. But try transitioning to any standard cadence and you hear its refracted curvature across the keyboard, like a musical score in a hall of mirrors.

The composition itself is also extreme in its starkness. A few deep drones loop around with incremental intensity, stretching out over 20 minutes. The first major chord change happens about three quarters in, after over 15 minutes. The cover art is bright and minimal, like a Josef Albers painting. Even its name, For Organ and Brass, recalls the modest functionalism of Baroque and early Classical. This would seem like an album written for a simpler time. But despite its deceptive simplicity, this music has a mysterious sticking power.

This may be in part due to the album’s emotional character. Its mood is not easy to describe, in part because it evokes two, almost contradictory, psychological states. On first listen, the album has an urgent, imposing quality. If the opening piece, ‘For Organ & Brass’ is a doom horn signalling impending apocalypse, then the closing ‘Three’ is a mournful reflection memorialising the end of history. The album begins with an intense anticipatory energy and concludes with pathos and a fatalistic acceptance. But after many listens, I now also find a cosy, homeliness to the record. Its warm chords and soft textures have become familiar comforts to me. I go back to them again and again for that safe, grounded feeling.

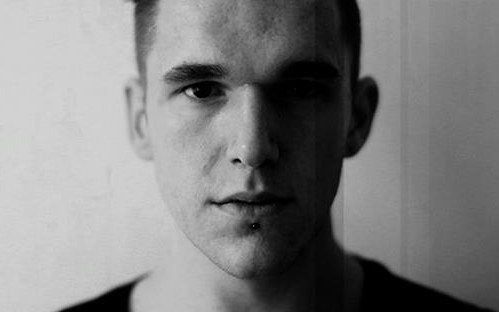

An album as rich in concept as For Organ and Brass warrants some unpacking and eight months from its release, Subtext have repressed the vinyl. To commemorate the occasion, we caught up with Arkbro to discuss the composition of a modern classic.

So how has this year been for you? It must be a strange experience to suddenly be in the limelight. I know you’ve been writing music for a while but now it seems like your name is everywhere.

That’s my feeling as well [laughs]. It’s been quite intense. The most difficult thing is to reorient yourself when you are suddenly put into a completely new situation. Until now, I’ve been more or less alone with my music, then suddenly lots of people who I don’t know are relating to it, suddenly I am not alone in the creative process. That’s a strange thing. It’s also difficult to stay grounded and focused when there are so many things happening and there are so many different directions to go in.

It must be odd going from a private realm to a very public realm.

Yeah — when you work on an album, and especially when you present it, you tell a story about yourself. And that story may be true to some extent, but it’s not the whole picture, you know? It can be very easy to lock yourself into this one story that you are telling the world. There are so many different stories that you can tell yourself and others about yourself.

I guess you’ve written lots of music that not many people have heard: pieces for guitar, electronic projects and so on. How did you wind up writing this piece in particular?

I wrote the organ and brass piece in 2014 for this organ in Stockholm that I found out was tuned in meantone temperament. I didn’t know much about that tuning at the time but I had been interested in tunings and intonation for some time and so I was curious to learn more about the meantone tuning, and I knew I wanted to write something for organ. In most of the music that I had made for guitar and electronics I had attempted to produce an organ-like sound. After a while I just thought, well, maybe I should just compose for an actual organ [laughs]. It was a liberating experience.

Can you tell us a bit about meantone temperament?

Since I didn’t know much about the tuning at first, I had to spend some time reading about it and then playing and listening to it. And after a while, I realised that some of the intervals in this tuning resembled, very closely, septimal intervals – the kind of intervals which La Monte Young famously used in The Well Tuned-Piano. The septimal aspect of the meantone temperament is not something which has been recognised historically, at least not that I know of. It is not something one usually learns about when reading about meantone temperament. It is more like a side effect of the tuning favouring pure or in-tune thirds.

That’s why meantone is normally used – for its beautiful major and minor chords with very clear and still thirds. You get all these interval characteristics by narrowing the fifth slightly, which means that meantone tuning does not have pure fifths. And this is the reason why I added the brass trio, so that the brass could provide all the pure fifths and seconds to the harmony. And I find it interesting that in the end, the sound of the fifths are almost more striking than the septimal intervals in this piece.

So what happened between then and now?

The piece was put on the shelf for a couple of years. I had a simple recording of that early version of the piece in Stockholm. I showed it to a friend of mine, who was working with James Ginzburg of Subtext. He secretly showed it to James, without my knowledge [laughs]. James got in touch with me and was interested in releasing my music. At the time I couldn’t really imagine how and what music I would be releasing, so it took some time for me to respond. Eventually I presented the idea of recording this piece that he had already heard and immediately it just felt so perfectly right to work on this project together.

I knew that I wanted to work with the Zinc & Copper brass trio in Berlin, so we decided to do the recording somewhere close to Berlin. At first, it was about finding the right instrument. I thought it would be easy, I assumed that there would be old organs in every corner in Germany but it turned out to be a big project. There were many people involved. Marc Sabat was very helpful and went on a quest to play different organs for me and sent me recordings together with his thoughts about the instrument and the room. Many organs were a bit too small or located in a room that was not suitable and so on. But finally, we found the organ in Tangermünde in Germany. I went there to play it and it just happened to be this incredibly beautiful 400-year-old instrument with the perfect sound.

How do you arrange horns to sound ‘in tune’ with a meantone organ?

Well the trombone of course has very flexible intonation. But the horn is a little bit more difficult. To change the intonation on a horn with a nice tone and clear sound, you have to work very hard with your lips and stomach and so on. You mostly have to use your hand inside the cone itself to change the intonation, but that also changes the sound. Robin [Hayward] plays a microtonal tuba, so he is perfectly flexible in intonation.

When did you first get interested in microtones as a musical device?

It was when I was introduced to the work of La Monte Young and the classical Indian tradition of raga. While I was studying at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm there was a wave of people making drone music and working with sustained tones. So I was introduced to it by friends, who also provided me with good methods for working with intonation. Very early on in working with electronic sounds I was introduced to SuperCollider, which is a programming environment for sound synthesis. When working in it, there are some very natural ways of working with rational frequency relationships – you are not restricted by having to deviate from something else (as with cent deviations from equal temperament).

So in a sense, with simple rational frequency relationships you are not really working with microtonality anymore, you are simply dealing with the most basic intervals, sort of taking them for what they really are, as being simple, not as complex deviations. So I believe the context in which I first started making electronic music was already favouring this kind of work with intonation.

I guess that’s one of the cool things about electronic composition – that you can more readily play with non-standard tunings. The very first synthesisers were very difficult to accurately tune because you just had a frequency dial, whereas with a piano you’re kind of forced to play ‘in tune’.

Yes, although strictly speaking the piano is not in tune, and I believe the 'out of tune'-ness is a big part of the sound of piano. When you listen to La Monte Young playing The Well-Tuned Piano it sounds like a completely different instrument. It’s the same with electronic sounds. If you have tones that are perfectly in tune, then the tones lock into each other and the sound will change, sometimes quite radically. At some points it can even be an unpleasant experience, but nevertheless an interesting one. A sound that is perfectly in tune is a completely unique kind of sonic experience, unlike anything else.

Can you tell us a bit about how you play the album live?

We recently played it in Stockholm, about two weeks ago. It was the premiere. It was a really nice experience — it sounds very different in a big room; it becomes a different piece essentially. We will perform it again at Rewire Festival in the Hague. It’s quite a hard piece to perform because every meantone organ is tuned slightly differently. The organ in Tangermünde was tuned to 486Hz and the one in Stockholm is tuned to 468Hz. And since that isn’t a common reference pitch, I have to write a score in 486Hz or 468Hz and then an additional score transposed to 440Hz for the brass musicians, with all the deviations from conventional intervals of their instruments.

So for every live performance I have to rewrite the piece and rewrite the score, so that the brass musicians can find their different fingerings. Part of the reason for the difference in tunings is that when they originally built these organs, they used someone’s forearm as a measure for the pipes, so they all vary quite a bit in pitch and tone.

I didn’t realise you get an actual organ on stage.

Yeah, at Rewire we get two pipe organs actually [laughs]. We will be performing For Organ and Brass on a smaller meantone organ and then we will most likely play a new piece including electronics, for a bigger organ tuned in equal temperament. With this piece I just use the fifths and the seconds of the equal temperament and then I add the electronics to make the organ sound more in tune.

I’ve heard that being at one of your shows can have a weird effect on the ears. Apparently due to the tunings, applause sounds like it’s underwater?! What’s going on there?

[Laughs] Yeah, I know. It’s weird, but cool. I don’t actually know why that happens, although I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about it. First I thought that it just happened when having listened to these extremely phase-locked tuned sounds. But then I experienced the same thing happen after listening to the recording of For Organ and Brass on a loud volume. I was quite surprised.

I guess your brain must alter in some way after adjusting to those unusual tunings. I remember reading about My Bloody Valentine’s use of extreme volume on stage and how an extended period of very high volumes can actually lower your neural oscillation frequency and put you into a mild trance state. You get high, basically.

I once flew to Manchester just to see MBV. I was right at the front with no earplugs. It was an experience.

Were you using microtones when you were playing guitar too?

Yes, I’ve always been playing with tunings on the guitar, tuning the strings to different chords. But I’ve mostly been playing open strings and harmonics and haven’t really explored how to tune the strings of the guitars so I can play on the frets.

And the septimal intervals are also used in blues, right?

Yes, blues singers often sing the thirds and the sevenths septimally, a lot lower than in the corresponding equal tempered intervals. It’s this low, heavy, sad sound. Very powerful. I love it. Definitely my favourite kind of interval.

Can you tell us a little bit about the ‘Mountain of Air’ piece you did after the album was released?

If I’m perfectly honest, the people I worked with got a little bit paranoid that the two pieces on the For Organ & Brass record weren’t “enough” somehow, and I guess I went a little bit paranoid too. Releasing an album can make you go a bit crazy I guess. It felt like going into a bubble and not knowing at all how to relate to the material. Like does it even sound good? Is this interesting? I don’t know. You feel too close to it and too far away from it to know how to relate to it. And I believe that feeling is even stronger when you work with such a reduced material, because if you start to doubt the sound or the chord that you chose, it feels like there’s nothing left.

So that’s why I started working with the recordings, to see if I could create something different with it. I remember opening SuperCollider and just putting in random numbers for playback speed and durations of overlapping parts of the brass recordings. I ran the code and this came out of the speakers. I thought that it meant that this material was really flexible so I tried going back to adjust some parts but the initial random numbers that I entered happened to be the only numbers that worked. So, I don’t really feel like I composed that piece, it just appeared somehow [laughs].

It kind of feels like Stockholm is at a very important musical juncture right now. There’s been so much great music coming out of the city in the last 12 months, it’s hard to keep up with.

Stockholm has been a very important place to me. I wouldn’t do what I do today if it weren’t for this context in Stockholm, these wonderful people around me. EMS is indeed an amazing place. You can basically go there and ring the doorbell, not knowing anything about electronic music, and get access to these amazing studios. You first have to go through a couple of courses learning Pro Tools and about electroacoustic music history and then you have access to the studios for lifetime. Fylkingen is also an important place.

There’s definitely a strong sense of community here, that you can feel more or less part of, of course. People are generally very serious about what they do. And even more importantly, I feel surrounded by artists and musicians who are clearly defined in their endeavours. It makes you want to be more transparent in your own practice and that is very inspiring.

'For Organ & Brass' re-issue is now available on Subtext. Buy here.

- Published

- Dec 12, 2017

- Credits

- Words by Georgie_McVicar