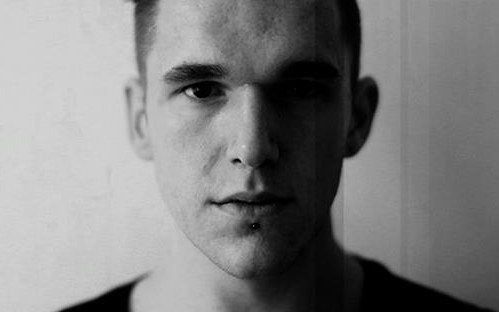

33 RPM // Graham Dunning

On paper, it doesn’t seem like Graham Dunning's music would really work. Stacks of vinyl are placed on top of one another, each triggering a different loop and culminating in a towering cacophony of juddering mechanical techno. It's almost like an elaborate magic trick. Indeed, there is an incredible sense of danger with his work, as if everything could go wrong with one wobble of the table. This tense energy propels the show forward, and gives huge payoffs when it works.

Dunning’s work is arguably part of the lineage in sound art that wishes to make a ‘return to the physical’, rediscovering the joys of pops and crackles in physical formats that contemporary music tries to hide. Christian Marclay is perhaps most known for this, famous for Record Without a Cover, an LP sold with no protective packaging such that each copy became a unique artefact with unique damages suffered in packaging, shipping and playing. Marclay was determined to remind us to look beyond the message and return our gaze to the medium.

But unlike Marclay, Dunning’s work is more than an art gallery installation. In other words, it’s actually nice to listen to! His upcoming EP, Way Too Much Time, is an intricate and considered record that would be welcome on any dancefloor. ‘Protest Dub’ in particular takes me back to my first listening experiences of those early Maurizio 12”s: it’s raw, gritty and groovy as fuck.

Ahead of his upcoming show with Edited Arts this month, we spoke to Dunning about vinyl, Jenga and 'mechanical techno'.

Your musical background is interesting insofar as you came more from Manchester’s noise-rock scene than any ‘sound art’ or art school experience.

Yeah I was playing in noise bands and I’ve always been doing the DIY recording thing. I guess I was in my late 20s and realised I’m not gonna make it in a trendy indie band [laughs]. I just happened to get more into experimental music and I started to realise that more of my mates were 'artists' than musicians per se. It just opens up a lot more options if you call yourself an artist. There’s no pressure to get signed by a label, for one thing.

Do you think you are seen more as an artist or as a musician?

I’m not sure - it’s interesting. My output has become more ‘musical’ I suppose. I started doing more abstract work with turntables, but since I started doing this ‘mechanical techno’ stuff it’s become a lot more beat-driven and accessible. But clearly there’s a big performative aspect to what I do so as well. I guess I’m somewhere in the middle.

Your new EP does strike me as being a lot less like the recording of an art installation. It sounds more like a classic 4-track 12”.

Yeah I sometimes feel a bit split with my work in that sense. A lot of my output is simply recordings and edits of live shows. But I also make stuff in the studio, where it’s built in a totally different way and I can take my time. It becomes more about how it sounds than how it looks.

Tell us about mechanical techno, is it a process? A genre?

Well it loosely just means music that I make with mechanical parts. All the sound that I produce comes from the rotation of the turntable. If the turntable is off, everything is silent. When I do mechanical techno, I set myself certain rules. I build the machine in a certain way. It’s also always a live mix, no multi channel recording. The records that I sample are always white labels that I get second hand. So by the very nature of the white label, the samples tend to be from other dance music. Maybe I could make nicer music if I was sampling old 78s or organ music or something. But the limitation to white labels is an important part of the whole mechanical techno process, I think.

Limitations are often what make music interesting in the first place I guess.

I’m super into all the DIY home recording approach to music, precisely because of its limitations. I love it when you can hear how a piece of music was put together: you can see through the cracks, in a way. There’s an Arthur Russell track where this guitar part comes in way too loud [laughs] and for whatever reason it was mixed that way and it’s super jarring and abrupt, but it makes it really intriguing and endearing at the same time. That one guitar part is on the edge of ruining the whole piece but somehow it works.

I’m currently editing down some new tracks of mine at the moment and I have the same problem. There’s a synth part in there that is just just way too loud so I’m having to chop and cut around it. But I like that those errors can force you to work in a different way. I could easily make a formulaic techno track (4 bars of kick, bring in the hats, 32 bars then drop et cetera) but then you fall into the same old patterns of behaviour.

I like a good sense of danger in music too. I want to feel like it could all go wrong in a second. Watching you build a tower of vinyls is like watching a game of Jenga or something.

Yeah I think that’s what people engage with in my work. I could continue to refine the set up and make it super stable and resilient to fuck-ups but it would be too safe. I’ve chosen to keep it more dangerous because that’s what keeps it exciting for me to play. This way of playing keeps me surprised even now. Sometimes a loose cable catches onto the contraption and everything slows down [laughs]. When that happens I can’t help but grimace or laugh, but then the audience can see it’s not all smoke and mirrors.

It’s amazing how the brain can find rhythm in those off-kilter loops too. You can find a beat in almost anything as long as it's got some repetition.

Yeah the random aspects of my set are my favourite things about it. Sometimes I can be totally lost trying to find the pulse amongst all of these arthymical samples, and I’m just having to concentrate so hard to work out where the kick should come in. Then as soon as you bring it in, it locks everything together. That’s a joy.

What can you tell us about your new EP, ‘Way Too Much Time’?

I wanted to make some weirder dancefloor stuff. I’m trying to explore my set-up and find the sounds that you couldn’t easily make with a computer. So I made some records that use prime numbers (1, 2, 3, 5 and 7) per cycle. Like for this track ‘Escaped Clank Replicator’, which is 5 against 7 against 3 time. It’s super wonky. There’s also a track on there called ‘Protest Dub’ that is a bit more spacey and dubby but in 3 against 4 time. An artist called Tom Richards also made me this optical trigger so I can make records with white squares on and the reader uses the visual cue to create rhythmical patterns. The title comes from a comment on the mechanical techno video that went viral, classic ‘this guy’s got way too much time on his hands’ remark.

I feel like the danceability of your music is often missed, have you ever played in more of a club environment?

That’s the point of what I do at the end of the day. It’s meant to be fun. I played at this squatted caravan park rave in South Germany once. It was the only place I’ve performed where they asked me what BPM I would play, because that determined how late in the night you would be on. I’d like to do more of that stuff to be honest. I like to get people dancing. I prefer to play in the middle of the room for that reason. I don’t want to feel disassociated from the audience. To be honest, I don’t really feel like I’m performing. I’m busy trying not to fuck up. It’s the machine that’s doing all the performance.

Graham Dunning will perform alongside Ewa Justka, Dane Law amongst many others on Thursday 22nd March. Details can be found here.

- Published

- Mar 18, 2018

- Credits

- Words by Georgie_McVicar