Flashback Signal // Atom™

Uwe Schmidt has many alternate identities. So much so, there are projects I've come across without even knowing it's him. There's been latino fusion covers as Señor Coconut, psychotropic ambient oddities with Tetsu Inoue as DATacide, glossy downtempo lounge musing as Erik Satin and countless others. Currently, he is best known as Atom™, a name under which he has consolidated his archive.

Schmidt grew up in Frankfurt, Germany, entering the world of music in the early 1980s, switching from drum kit to drum machine after hearing a Linn Drum on the radio for the first time. Producing work influenced by the emerging techno and trance scenes, he developed a partnership with Peter Kuhlmann (better known as Pete Namlook), putting out early works on the legendary FAX (or FAX +49-69/450464 for the pedants among you).

He also set up his own FAX subsidiary, Rather Interesting, in 1994. The label acted primarily as an outlet for Schmidt's own productions, allowing him to experiment with a plethora of different genres, from glitch to Latin America-inspired electronica. Schmidt's relationship with Latin America deepened upon his relocation to Chile in 1997, a move he made in an attempt to isolate himself from the increasingly marketable electronic music scenes consolidating themselves in Europe.

Following Kuhlmann's sad passing in 2012, Rather Interesting closed after 18 years of operations. Schmidt created a new label with Andre Ruello aka Material Object, another collaborator of Kuhlmann's, a couple of year's later under the name 'No.'. The imprint's aim is to remain 'independent from classification'; most recently releasing Intrication from France Jobin, an album inspired by the reactions of subatomic particles.

We caught up with Schmidt to discuss the founding of No., his relocation to Chile and the unstoppable march of Western pop...

Tell me a bit about how ‘No.’ came to be… How did you first meet Material Object and what made you want to start a label together?

I got to know Andre while he was doing artwork for Pete Namlook's FAX label. We were in touch very briefly through email, exchanging ideas about artwork - nothing special really. Every couple of years he would send me some pictures of what he was doing, or he would say hello. I hadn’t really met him, and in those days he was actually much closer to Pete than I was. We kept working together me and Peter but we weren’t really talking much. Everyone was busy doing their own thing I would say.

When Peter died, Andre was the person who told me - he notified me that morning. He was the only link really, between me and Peter I would say. I think without Andre no one would have told me that quickly. That kind of bound us together a little bit, in that moment. We kept talking about things related to Pete - very practical things like who was in charge of certain things. Aside from being friends I was doing business with Peter. It’s like a second level to when somebody dies - suddenly you have business considerations. I had to figure things out on that level. It’s a little bit odd - when somebody dies you don’t want to think about that stuff but at some point you have to. Andre had a little bit more insight into that side of things.

We met a couple of times in Berlin and a few other places. We both felt like it would be good to create a platform that would be a place for a certain type of music that we felt didn’t really exist. It’s not necessarily an ambient label I would say, we wanted to create a platform where we could put out stuff we liked independent from styles or classifications.

In the bio on your website, there are a lot of bankrupt labels mentioned along the way (such as Mille Plateaux). Have you learnt lessons from the mistakes of others so to speak?

Not really. A lot has changed since I started making music up until today, especially on the business side. I would say it’s completely incomparable to what is going on today as compared to five or ten years ago. That said, I think there is a lot you can learn from that - everything is in flux. On a personal level there are definitely things I have learnt. It’s more about with whom I want to work.

One of the things I told Andre is that I'm not interested in bureaucracy. I really want to see No. as a musical endeavour. I don’t like to think about music as a product and all that. I want to make music and release it without a big fuss, without all the promotion and business considerations which leave a strange aftertaste I think. You make music and then it suddenly turns into a product. Of course you have to do it to a certain degree, but I really didn’t want the operation to be transformed into just that. Often when you do a label you suddenly become like a banker or something. You’re not really thinking about music anymore you’re thinking about other things.

You mentioned earlier that you might not have heard about Pete’s passing if it wasn’t for Andre. Do you really feel that cut off from that world living in Santiago?

Yeah I think so. Pete wasn’t a friend I was in touch with on a daily basis and we didn’t share much of a common group of friends. There were a couple of people like Andre and David Moufang [Move D] who I know, but we weren’t involved that much. There weren’t many direct links.

Living in Chile, I’m not reading the press, I don’t watch TV… I try not to consume any external media as much as possible. If something really important happens in the world of course I’ll receive it, but maybe a day later or something. In the case of Pete, I think someone would have told me, but it would have been a few days later and through a very indirect route.

I’m working hard on my isolation. With all the positive things about the internet, it’s also brought information closer to me; I think it’s way too close. I don’t like that part of being connected. When I moved to Chile it was slightly pre-internet. Not many people had it. A year or two after, the connection happened but when I moved here communication came through phone calls or sending faxes or letters.

In that sense I don’t really see myself as being part of some kind of scene in terms of music. Those discourses in terms of genres I found them more of a problem than a solution. I find staying neutral and working on your own ideas much more useful than having to deal with other people’s ideas. The fatal thing with an idea, is that once it is in your head you can’t get rid of it. Even neglecting or rejecting it becomes a thing.

It struck me there are many parts of the world you could isolate yourself in. What has kept you in Santiago all these years? What do you like about living there?

Well, Chile is physically really far away from everything so the mentality of the people is different. I always say it’s like an island mentality - people are really isolated. They have been isolated both historically and physically for a very long time. When you are here, you feel like people aren’t really connected. If you live in other parts of South America, even Argentina for example which is just around the corner, they are much more connected to Europe. In architecture - how they build their cities - the things they talk about and how they see themselves. With Chile it’s a little bit different.

When I first came here there was no connection to the outside world possible really. Being a foreigners was something rather new. People would look at you in the streets because you look different.

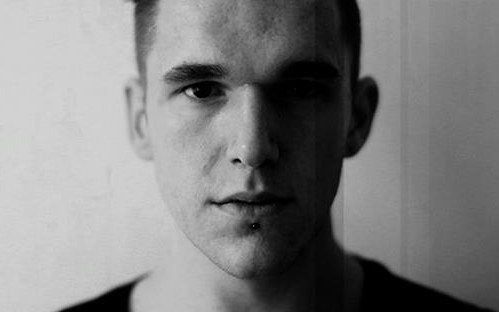

Atom™ at Decibel Festival, 2011.

You moved there in 1997, at which point Pinochet would have still been leader of the Chilean army (just). I’m guessing you must have seen a lot of change politically.

I think he was gone by the time I got there but you could still feel that and you still can today. It was much more isolated in that sense. When Tetsu [Inoue] came here in 1999, he was walking around the neighbourhood and someone shouted ‘chino’ out their car, which doesn’t actually mean Chinese - Chilean people call anyone Asian 'chino'. He was really offended because as a Japanese person he thought it wasn’t nice to call him Chinese. But he stood out as an Asian tourist.

It has changed quite a bit, I don’t think that would necessarily happen today. When I came here - people would honk their horn at me and want to talk. You would have weird experiences on the streets. I liked that at the same time and found it very inspiring to be disconnected. In that sense when you said there are many places where you can be disconnected - I’m not so sure. The world is big and there are many places you could cut yourself off - certainly if I moved to central Africa I would be isolated… I was looking for a certain balance between isolation and being able to do my thing. Being far away but not on the moon or something [laughs].

I am a big fan of your Datacide project. I read you recorded the first album stopping off on New York on your way back from Costa Rica. How did you and Tetsu first meet and how long did that particular album take to make?

That album was recorded really quickly at his apartment in New York and partly at my place in Frankfurt. Tetsu was a friend of Station Rose - an artist couple from Vienna. I was supposed to produce an EP for them in my studio in ‘91 I think. Tetsu was friends with them. I found out he was making music as well and we decided to work on a track together. On Station Rose’s first EP there’s some bits of Tetsu on it.

When I went to Costa Rica I asked him if I could come over to stay for a couple of days. That’s when we did the first album. It was done really intuitively I would say, not much planning. I was very much into hard techno but also ambient and more obscure derivatives. We both got much more interested in abstract electronic music and the albums after that we recorded in Frankfurt. We became close friends and talked a lot on the phone.

Ondas struck me as a particularly interesting listen - can you tell me a bit about the recording process? There’s lots of avant-garde sort of interludes (like the lip trumpet solo, recordings of footsteps etc). Was the approach different to DATacide I/II?

I think both Tetsu and myself were trying not to repeat ourselves. When working on something we would have a brief talk before the recording; we realised we were really in sync with each other.

It was the same case with Ondas. It wasn’t really a concept, but we were both interested in things that happen when you are tripping - we were trying to extract those experiences into an audible scenario. We were always interested in how to go from one scene to the next. Suddenly we both got really fixated on those really harsh cuts that happen when you’re on acid. When you’re totally into one thing and then it flips - like you’re flipping a channel - you’re out of it and into something else.

A lot of that information was stemming from trip memory - things that impressed both of us about the experience were very similar. We were certainly both interested in making ambient music trippier. The classic 'ambient sound' doesn’t have much to do with psychedelics - it’s more to do with Klaus Schulze and these people. We were interested in developing something different.

Do you have a love hate relationship with pop? You do a lot of pop covers as Señor Coconut and as part of LB. At the same time there’s a lot of comments about the state of mainstream music in HD…

Well I really like well done pop music. The entire topic of what pop is I find an interesting phenomenon. There is music made for popular consumption which needs to be compatible with a massive amount of people. It has to resonate with the masses; in that sense it’s always a mirror to what’s going on. In that sense it’s a very complex system, it’s not only a mirror of the listener, it’s a mirror of the market because it’s a commercial enterprise; I wouldn’t even say it’s a necessarily musical enterprise.

When something good is being produced I really like it. Currently though, I’m not very interested by what’s going on in the world in general, and this reflects into pop music as well. HD uses a pop format in order to make certain types of statements. If I tried to revisit that state of mind, I would say I’m a little bit bothered with the fact electronic music has turned into that kind of neutral, abstract zone of art that feels like it doesn’t have to comment on anything.

I’ve noticed how marketable it’s become in recent years. You see producers you consider as experimental now making music for adverts - it’s been kind of hijacked in that way...

With HD I was trying to open up a certain attitude being very aware of the difficulty of making any kind of statement nowadays. I was very aware of the contradictions within the work. I was more interested in making music that made a certain statement even if it wasn’t coherent - than not making a statement at all. I would perform the music live and someone wouldn’t like it. Someone would come up to me and say it was a really superficial way of seeing things. I liked that much more - being able to talk to someone about that.

The word hijacked that you used describes it pretty well I think. I was looking back at - maybe ten years ago - many old things I had done. Very often when making music, I’m perceived in relation to other stuff that surrounds me. Suddenly I realised I had to defend myself in a surrounding that had kind of hijacked me. I was thinking, what do I have to do with this? What is the relationship between what I’m doing and EDM let’s say?

You have that ‘Insulting the DJ’ track which seems to reflect a dissatisfaction with a lot of conventional club music.

Certainly. It’s weird - you start making something under a certain premise and slowly it gets infected by something else. You still like doing it but you are part of something different suddenly. You have to react to that. I sort of created my own world with things like Señor Coconut and then I realised after a while it would be nice to go back to things like ambient and techno.

Techno has become such an industry and there are so many boring things being produced. I distanced myself from that because I didn’t like the surrounding. I didn’t like the idea that it had been ruined for me by something else though; with pop it’s a bit similar.

One of the things I’ve noticed doing music writing is how simple the story needs to be for writers and consumers. I did my dissertation on what most people know as ‘krautrock’ - it always struck me as a good example in that most of those bands didn’t know each other and they sound wildly different. But still the press had this impulse to try and band everything together.

I think this has always happened with music. There is always the impulse to bind everything together and give it a coherent analysis. I think the same same thing with punk. I only see a couple of bands doing similar things. Maybe you can say there is a common attitude but I don’t think punk existed as such. I often have problems with those classifications but at the same time find them very interesting. A lot of the things I was doing with Señor Coconut was playing around with genres; breaking them up and combining them. The classifications stop making so much sense.

For someone who makes electronic music today, you are immediately classified into a genre. This happens every time I talk to young people who are starting to make music. Even before they have made a single tone, they know what they want to be, which is weird. “I want to be a D&B artist”. It’s like, really?

I sometimes wonder what effect this has on localised music scenes - say things like gqom which are suddenly put in the media spotlight in Europe.

It’s a problem of course if a scene or a genre is being discovered and exploited because it necessarily means this scene becomes part of an economic timescale. Those timescales are getting shorter and shorter. If you remember at the beginning of the ‘90s there was a new hype every year. Someone would come up with 'bleep' or something, and then 'clunk'… The cycles became shorter and shorter until 15 or 20 years ago the cycles became so short that the whole operation became useless. Eventually everyone threw up their hands and admitted we don’t know what’s going on [laughs].

I found that really positive. Finally they gave up! Now of course there is a certain appetite for new products. I’m not living in Europe so I don’t know what’s going on. The old scenes are exploited - how much movement can you generate? You burn those genres basically. When you, for example as an artist approach the media or a festival, there is this permanent attitude where they go “yeah but is this new?” You go “well I don’t know, it’s me. How new can I be after so many releases!”

I always found that very disturbing. No one would go to you as a journalist and say why are you just asking me questions like in the old days - come up with a new kind of journalism... But for the artist you are constantly being asked to come up with something incredible every six months.

It’s also like - what’s the difference if something’s new or you’ve only just come across it?

Totally. My favourite example is Sun Ra. I always say that if Sun Ra had not been discovered by anybody when he was alive he would have just been a crazy somebody and nobody would give a shit. The fact that he was discovered and absorbed by free jazz and even people like Miles Davis - who transformed his ideas into something popular - he then in a retrospective way became somebody who was like ahead of something. But he wasn’t really ahead of anything, he was just being himself. In my opinion there is nothing really new or old about any artistic creation that is genuine.

I think that pop has moved into its own realm a little bit. It’s come to that weird frozen place where everything sounds the same wherever you go on this planet.

It links to how ubiquitous the exportation of American culture has been. You can go to any country and buy a coke for example.

I was sitting in a cab in Khazakstan driving back to the airport at 5.00am on a Sunday or something. The guy has the radio on and it sounds like any pop music anywhere but sung in Russian. I really understood it and where it came from and how it was made. I could be in another cab somewhere totally different and the same song but slightly different would be playing. I find it interesting how electronic music does or doesn’t deal with that. I’m not saying when I started making electronic music it was political or anything, but it felt more daring maybe.

I don’t know who said this, but there is a saying that the difference between art and design is that art is challenging. There’s nothing bad with design - everybody loves design, but it’s not art. Especially festivals who do 'avante-garde' art - very soon you realise if you talk to them their approach is not that daring. Often the entire enterprise is tied into that very comforting machinery which you can feed eternally with the same content more or less.

Normally the problem is directed towards the artist. But the artist is totally embedded into a much bigger picture. As an artist you are being selected or rejected and it’s a very complex mechanism. I always see the problem being fed back to artist: ‘do something radical!’ I include media and journalism and festivals and venues and everything - they’re all playing along. It’s very easy from any perspective outside the creative one to throw the problem back to the artist.

When the music industry problems started around 2007; when labels were going bankrupt, distributors were closing down and festivals were disappearing, there were many artist friends I had who stopped working. I was on a panel around that time and we were asked what should be done. It was the first time anyone asked the artist in the 20 years I’d been working. It’d never been a question and now it is - why is it me being asked? Suddenly no one knew what was going on. Suddenly this thing turned around.

- Published

- Apr 15, 2018

- Credits

- Words by Theo Darton-Moore