Cross Pollination // Mats Erlandsson

The first time I met Mats Erlandsson I didn't know who I was talking to. In Stockholm's EMS studios, where Erlandsson works, we chatted briefly about the studio and the limits of radio broadcasting. My only thought was 'this studio engineer seems a bit friendly', but my stupid brain hadn't put 2 and 2 together. It was only afterwards that I realised 'Mats' was 'Mats Erlandsson', whose releases with Posh Isolation the year before had been on near-constant repeat.

Erlandsson's music is often difficult listening. It almost sounds like the sonic representation of conflict. Competing drones tackling one another in a tooth-and-nail struggle for survival. The sound sources are also obscured, as if purposefully vandalised out of recognition. Before reaching your ears, it's as if each instrument has endured a grueling post-production process. Every sound is twisted, stretched, flattened, cut, made to work against itself. Not sound speaking for itself, but sound tortured into telling the truth.

Some of Erlandsson's most interesting music also comes through collaborative work, most notably with the brilliant (and criminally overlooked) Yair Elazar Glotman. Last year, they released Negative Chambers together, a welcome return to ambient done the acoustic way. The album boasts an impressive range of instruments: gimbri, violin, karkaba, miniature cymbals, cello, harmonium, steel string acoustic guitar, zithers, transistor radio, Tibetan singing bowl, amplified plate & piano frame alongside Glotman's contrabass. Last year also saw the release of a dazzling new collaborative project, Dufwa, with Maria W Horn, on Horn's XKatedral imprint.

Prior to our chat at the end of last year, Erlandsson sent me a text he had written on his thoughts on the role of media today. Opening with the line 'context is only a salespoint', he expressed his frustration with the gimmickisation of music. In an ever-crowded online market, recognition often requires a kind of musical 'schtick' to be remembered, a conceptual ornament for the easily distracted, a unique selling point, a product. But how does this impact the kind of music being made today? Are we finally heading towards the nightmarish conflation of music and meme?

In this long-form 'meta-interview', Erlandsson and I talk about our discontent with interviews and music marketing in general, as well as CC Hennix and the formation of the Stockholm Drone Society.

Before this interview you sent me a bio text about your thoughts on music promotion and marketing. Can you expand a little bit on your thoughts here?

That was my sincere attempt at writing some promotional text for this new record [laughs]. I found it so hard since I was constantly second-guessing myself I just decided to write about what was going through my head instead. It’s an odd paradox criticising the marketing dimension of music in websites, magazines, social media and so on while at the same time operating in that field, although on a very small scale. At the end of the day, I did make the music and I insisted on releasing it. It didn’t just magically happen, it’s not like an accident, you know? And I do want people to hear it, so how can I earnestly critique the way music promotion is structured and published?

Having a gimmick or eye-catching novelty attached to some music is gold-dust for people like me because it’s easy to write about. But it means we’re slowly veering into a resurrection of ‘conceptual music’, which is worrying...

Yeah, I had a weird experience releasing my first album with Posh Isolation, Valentina Tereshkova. Originally that was just a name of one of the tracks which ended up being the album title but all of a sudden people were saying I had made a Russian cosmonaut concept album. It was fun to watch in a way because from my perspective the way it came together was entirely a media and PR construction. It had nothing to do with the music itself, it was just a narrative constructed from these bits and pieces. On the other hand, of course the seeds to that narrative were already planted in the release by having two track titles that related to Tereshkova so it is not like I couldn’t see that coming.

Do you think people read too much into the concepts behind albums?

Anyone can read as much or as little into an album as they like. It was just funny to see how well established this narrative became in the marketing of the album, without any real substance besides a name. The problem I think is that the experience of hearing music is so heavily tainted by preconceived ideas. So when a journalist propagates a theory behind your music, it has a huge influence on how people hear it.

I guess for me this is less of a problem than for someone working within a very clearing defined space — like if you are devoted to always working with a certain instrument or process (two examples that come to mind are the Buchla modular and Just Intonation just in terms of how strongly they tend to define the outcome). It seems to me that the downside in that case will be that your work is always heard through a filter of that conceptual framework, which becomes impossible to disassociate from.

Do you believe in this idea of the ‘death of the author’ in that sense? Does your intended purpose count towards the meaning of the music or is it entirely irrelevant?

They’re just not the same. It’s just like being on different sides of a membrane. I have way too much insight into the music I make to make a good judgement on it from a listeners perspective. When I listen to other people’s music, I habitually try to break down how it was made, not necessarily with my full attention but like a process running along in the back of my mind. Whereas with my own music, I remember more or less how it was all made, since I was there. So the illusion is already broken. For that reason, I think the artist is always the worst judge of their own practices. I guess what this means is that for me the making of music does not serve the same purpose as listening to the music of others, which is probably a health approach.

It’s interesting how this concept applies to a live context. I read that Mozart’s concerts were full of audience members applauding to themselves during parts they liked. It allowed for an active, vocal interpretation, basically. It’s only recently that the audience is expected to sit in respectful silence until the piece is over.

Well, the sit-down-and-be-quite-until-its-over-format has more to do with 19th century bourgeois concert house culture than with Mozart who had to operate in a context of being funcional- or background music or full-on entertainment shows.

I think one of the most widespread misconceptions about music is that it can communicate an idea from the artist to the audience without the idea being corrupted in the transference. John Cage for instance was super surprised when he realised this was wrong. There’s a chapter in his Silence book where he says his world fell apart when he realised he could not accurately express his emotions in music to an audience, because they just wouldn’t get it. For me now, that just seems like the most obvious thing in the world, although it took me a long time to wrap my head around and accept. Music as a medium just really isn’t suitable for transferring emotional information.

And yet music is talked about as this universal language

That’s true but I think people are just communicating with themselves. Which is fine, I don’t see that as anything negative at all, it’s just a feedback loop.

The same goes for applause I guess. You’re not so much expressing gratitude towards the performers but more to yourself and people around you — it’s an expression that you understood it and you enjoyed it.

It’s also a cultural thing — applause is a reasonable amount of expression within the confines of the traditional concert hall. You can just use your hands, you can remain seated. You don’t need to do anything too extravagant. I was recently thinking about the applause in jazz, which comes after the piece is finished but also within the piece, after each respective solo. When I was kid, I didn’t really understand when a solo ended since I hadn’t been conditioned to understand that musical form by ear, so the only clue for me was the applause. So applause has this structural purpose too.

It feels like Stockholm is at a very important cultural moment right now. I have asked a few people why this is and the answer I always get is always a material one — you have access to these great institutions like Royal College of Music, EMS and Fylkingen — but they’ve been around for a long time. So what’s changed?

Well it’s true that we have these institutions available which I guess makes a difference in terms of being able to practice one’s craft in a serious setting. But what they do that is specifically interesting is this continuum between them. So the borders between the Royal College of Music, EMS and Fylkingen have slowly became less clearly defined in terms of aesthetics. At a certain point in time there was a lot of cross-pollination between the school, the studio and the stage.

Apart from the old institutions we already mentioned a more recent development that to me seems to have had a huge impact on the musical landscape in Stockholm are small independent groups/organisations like Drömfaktulteten, Masskultur, XKatedral and to a certain extent perhaps also Sthlm Drone Society (SDS). Then there are also people how function kind of like one-person-institutions when it comes to arranging, like John Chantler or Robin Smeds Mattila. I guess a main characteristic of the city at the moment is that all of these groups actually don’t have that much in common in terms of structure or function, and they span a pretty wide array of genres, but at the same time coexist within the same environment.

How did the Stockholm Drone Society start?

The Stockholm Drone Society was started by Maria [W Horn], who basically sent out a mass email to a bunch of people wanting to formalise something around all the drone music going on in the city. So the SDS thing was not the start of an interest in that type of music but rather a formalisation of something that had already been going on for a long time.

My first real contact with drone and noise music in Sweden came about through Daniel M Karlsson and Jonathan Liljedahl, first at the school of composition in Visby and then later at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm. Their music had an enormous impact on me at that time and I was always sort of following them around — going to their shows and trying to figure out what their influences were. I’d been super obsessed with Daniel's music for years prior to that but that’s a whole other story. At the time we became friends, Daniel was very interested in the music of CC Hennix, who at that point in time was pretty much completely unknown outside of a small circle of people — this was before the release of The Electric Harpsichord and before that article in The Wire which made her a bit more famous. I remember the only music which was available to us at the time from her was an .mp3 of a very bad recording from a Dutch radio show which had parts of The Electric Harpsichord as well as some other pieces from the concerts at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1976.

Anyway, I guess there is this lineage in terms of influence and interest in slow long form music that runs through a loosely defined group of people who at one point or another were affiliated with the KMH or Fylkingen. Some names that stand out for me in this regard are Daniel and Jonathan, Mattias Petersson, Isak Edberg, Maria W Horn, David Granström, Ellen Arkbro, Marcus Pal, Caterina Barbieri, Marta Forsberg and Kali Malone.

And CC Hennix was at EMS for a short while, right?

Yes, Hennix was working on music at EMS during the seventies - both doing some form of text-sound composition and also helping La Monte Young realise one of his compositions using the computer studio there. Hennix was also involved in Fylkingen during this period before she left Sweden in the late seventies.

Another Hennix-related thing that ended up having a lot of influence 30 years later was the Dream Music Festival of 1976 which was arranged by Hennix at the Moderna Museet. That thing was a festival of continuous sound with a lineup that is pretty amazing — La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Hennix and works by Terry Jennings. For me, this event took on pretty much mythical proportions especially since I could only find sparse documentation of the whole thing and it seemed so unreal that long form music could be presented in such a high-culture setting without compromise.

It seems like there is a quite widespread interest in La Monte Young in Stockholm.

Yeah — for me that also came from Daniel M Karlsson, but by accident. This was during that time when I was sort of studying the music of Daniel and I found this folder on a computer at school after he finished with a bootleg La Monte Young collection [laughs]. I’d been aware of La Monte from before but this enabled me to study the music more in depth. Some time after this Marcus [Pal] and Ellen [Arkbro] took their La Monte-fascination to another level by actually going to study with him in New York. This still seems completely surreal to me.

La Monte Young’s project with drone music was a predominantly spiritual one. To lift people into this psychic heaven. But what is the use of drone music today?

I don’t really believe that music needs to have a use that goes beyond the personal. I guess you could view drone or long form music in some political sense, but then again all musics are political if you look at the practitioners. The most banal political aspect of drone is that it contrasts the experience of everyday life. But that’s a little too easy, it’s kind of like saying drone is the music equivalent of going to a spa.

But it’s also pretty unsellable. It’s inherently fringe. Having music that operates on another timescale is also interesting and transgressive for me. It doesn’t conform to the medium of entertainment. Even at festivals like Atonal or CTM, the music is packaged within a digestible timescale: a standard 60 minute set which means they can’t really accommodate music performances on the scale of someone like La Monte Young or CC Hennix, since both of them compose works that are theoretically infinite.

What are the Stockholm Drone Society shows like?

Well, the main thing that have set them apart from other shows is the length — all the shows we’ve done where around 8 hours or so. Since all of these shows have been in the form of extended showcases they consisted of a string of performers each playing a piece around 60 minutes per person. So that ends up being a long suite of music in a similar vein but with different characteristics depending on the composer.

Most of the shows we’ve done have been in Mimer during Norbergfestival. I think it works well for someone who is not familiar with drone just because of Norberg’s setting in the mine. So people get to spend the night in this spectacular setting within Mimer which I think taps into this childish fascination with being able to stay up late as well, at least for me [laughs].

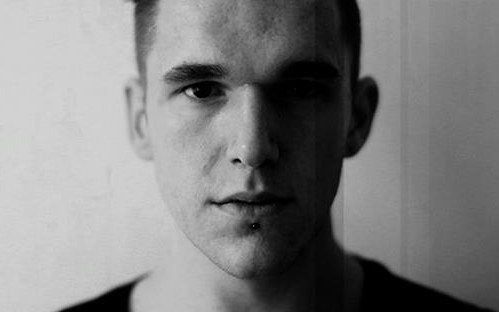

Mats Erlandsson & Yair Elazar Glotman, photo by Camille Blake.

Mats Erlandsson & Yair Elazar Glotman, photo by Camille Blake.

I like the framing of your album with Yair Elazar Glotman as “dislocated ‘folk’ music for the current dark ages”. So that has a political function.

Yeah, I guess so. But then again that narrative is also something that came pretty late in the processes. For me the importance of that album personally had to do with me being able to go out of the area where I felt most comfortable and push myself to do something different, in terms of how the music sounds, the recording processes and also dealing with the idea of collaboration. At that point it’d been a long time since I had done any formalized collaborative work with anyone so when Yair suggested we’d work on music together I couldn’t really see what we were going to do — I was kind of nervous but still excited to get to work with my friend.

I’m really happy how that album turned out though, and I feel proud I was able to function on that level as a musician. As a guideline while we were working we liked playing with this idea that we were writing some very constructed folk music, like murder ballads or something: highly contextual music but without any actual context, only loose imaginary context. It ended up being very associative music, just down to the instrumentation. On occasion it is almost borderline ‘Game of Thrones’ in its association [laughs].

There’s some really unexpected instruments on it, like the gimbri.

Yeah that’s Yair’s. He was really into playing it when we started writing that album. I think the main reason for the instrumentation being what it is would be that we’re not really using any electronics for generating the sounds. If a piece needed some long sustained tones or something metallic in the high register or whatever we had to figure out what we had on hand in terms of acoustic instruments that could fill what function.

So that’s what led to a lot of these prepared zither things or sustained harmonium chord progressions. Again, doing that had a big effect on me personally since a lot of the ideas on instrumentation spilled over into my own music. Especially the prepared and sustained zither stuff ended up really shaping the sound of this album that’s coming out on Portals Editions in the spring, although that might not be audible straight away.

What can we expect from your performance at Norberg with Yair this year?

I think it’d be good not to expect hearing music from the album, other than that I have a hard time trying to control anyone’s expectations. We’ve been asked before by people if we were planning on performing in conjunction with the album release last year but I always thought it’d be weird to perform the music from the album as a duo since it’s very much a studio work in terms of instrumentation — a proper live performance would require creating a fairly esoteric ensemble and doing some extensive transcription and rehearsal work, so basically it would be impossible from an economic standpoint.

Anyway, when we agreed to do a performance for The Long Now in March of this year, we decided to compose a new long-form piece that’d be possible to perform as a duo while retaining the instrumentation and textural characteristics of our previous work, this time working from a base of electronically treated zither and harmonium recordings in conjunction with extensive tape manipulation. The upcoming performance at Norbergfestival will be the second iteration of this work, which I hope we’ll continue to develop throughout the autumn.

Mats Erlandsson will perform at this year's Norbergfestival, alongside Yair Elazar Glotman. Tickets can be bought here.

- Published

- May 17, 2018

- Credits

- Words by Georgie_McVicar