The Furnace Room // Zimoun

Photo by Aoki Takamasa.

Swiss artist Zimoun constructs sound sculptures which challenge the eye as much as the ear. From his studio in Bern, Zimoun makes use of the most rudimentary of tools: wires, cardboard boxes, plastic bags, cork balls and small electric motors are deployed in their hundreds. The structures he creates are so large they often impact the architecture of the gallery spaces they occupy. A devoted reader of John Cage in his early years, Zimoun’s primary interests lie in simplicity, repetition and the relationship between sound and space.

Since 2003, Zimoun has also co-run Leerraum with graphic designer Marc Beekhuis. Described as a ‘platform for creative exchange’ rather than a label in the traditional sense, Leerraum is characterised by similar themes to Zimoun’s individual output. The majority of its releases are delivered in surround sound, some utilising ‘ambisonic’ techniques, whereby audio is even directed from above and below the listener. Each batch is paired by a photography series from select visual artists, before being sold as single editions rather than produced en masse. This said, Zimoun and Beekhuis are keen for the label not to become too exclusive, making each recording available to stream on their website.

With recent releases including a kosmiche-style synthesiser jam from Mihalis Shammas, a minimalist dub headtrip from Matt Spendlove, aka Spatial, and several Zimoun collaborations, we decided to catch up with Zimoun to discuss the aims of the label, function in architecture and early sonic experiences.

Tell us a bit about how Leerraum first came to be.

In 2003 graphic designer Marc Beekhuis and I founded Leerraum. We have known each other since we were teenagers. We shared a common interest in various forms of minimalism, in simplicity in general, in reductive methods and principles. One day Marc mentioned the name Leerraum as a possible title or ‘frame’ to do something based on those interests. Leerraum is the German word for various things related to emptiness. We felt it greatly fitting of our interests, and so Leerraum was born…

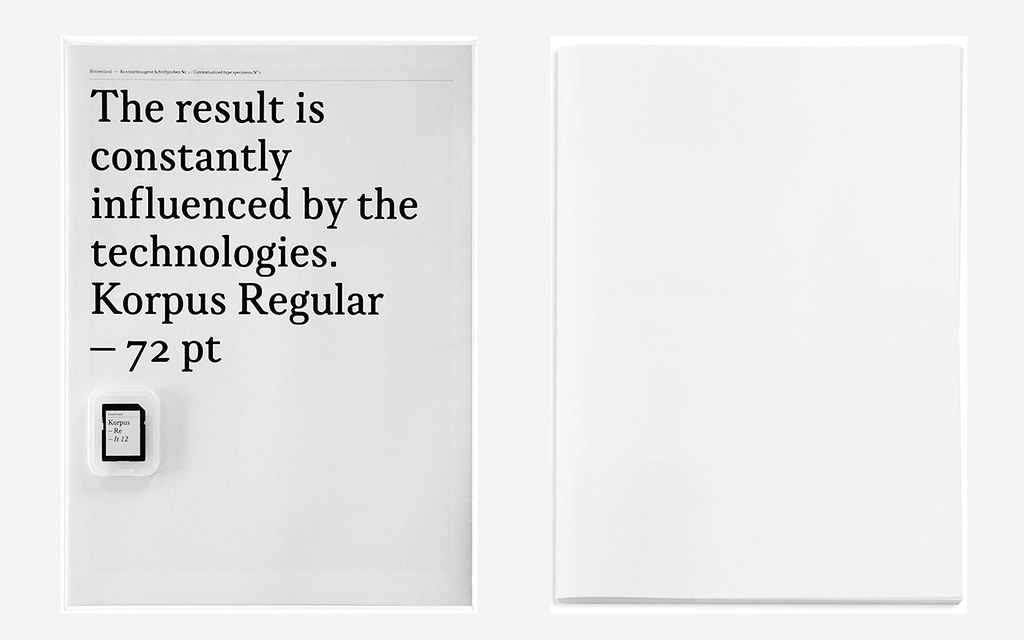

We have been publishing audio works in a series since the beginning, and each of these series are based around images by a visual artist. The current series is based on Philipp Schaerer’s amazing Bildbauten. Between these series we release objects and other works which do not relate to a series.

...in that moment both of these worlds merged together. You hear what you see and you see what you hear...

I’ve seen you reference Leerraum as a ‘platform for creative exchange’ as opposed to a record label. Given this, is its commercial success important? If not, how do you measure its performance?

Since we have been focusing on very specific, ‘niche’ works since the beginning, we have never had any commercial ambitions or expectations for this project. If something is sellable or not doesn’t matter here. For us it is about content and focus – about collecting and curating. It is also about retaining the freedom to do what we want to do and keep everything fully independent. We appreciate it is and always was, a very small and specific project.

Some of your early releases were in batches of 100-1000, now most are just one edition. Explain how you arrived at this decision and how the releases are typically sold.

We did small pressings in the beginning and those have got even smaller over time. We started to question the border between ‘art object’ and ‘storage medium’ or ‘package’ – between material and data. Questions about value also appeared. We’ve only produced one physical copy of the audio works for a while and we handle it like any other piece of art. The single editions come with a signed certificate; signed by the artists who did the audio and the cover image, as well as by Leerraum.

All published works are available for free streaming over at the website, in great quality, full-length and even in multi-channel if your device is connected to such a sound system. The signed physical copy is for the art collector, the free online stream for the community.

I liked that about Leerraum - it stops the short run releases feeling too exclusive.

Even if the physical copies are very exclusive and based on the idea of owning and collecting an artwork, we always felt its wider availability was important too. We do not intend to give away the works for free, but we still want to make them available as a stream for those interested. Again similar to a painting – one person can own the original, but many still know about it from reproductions on the internet, books etc…

The art itself is available for everybody that way, without losing the idea of the unique original piece. There are some serious thoughts behind this, but also some playful and ironic ones too. In the end Leerraum is more an art project itself, rather than a conventional form of label or publisher.

It’s nice that you can’t skip through tracks on the website which encourages you to listen in full. How do you think the way we consume music today has altered our listening habits?

It’s an interesting questions but I’m not sure I could say… Probably the tendency leans towards speeding everything up – listening for ten seconds and then pressing the ‘like’ button or not. We focus more on slowing down.

Many of the works we publish can be listened to as space – as a room or as a sculpture, rather than as ‘music’ in the conventional sense. More like a building which you can enter and look around. Often there isn’t much changing over time in these compositions, but there’s a lot to discover within their micro-structures. It’s similar to listening to the sound of a river. You might think it always sounds the same at first, but once you start to listen to it actively, you realise how deep and rich the sounds are.

Ambisonics and surround sound are a common theme in Leerraum releases and your own art installations often immerse the audience in the experience completely. Where does your interest in these ideas stem from?

Somehow I was always interested in sound as a three dimensional and spatial experience. Sound defines space, and space creates sound. Leerraum started in the early age of 5.1 home cinema systems – people slowly started to buy surround-sound systems at home to watch movies. That way the ‘potential consumer’ got technically able to listen to multi-channel compositions or speaker-based sound installations at home. Several of the artists we worked with had also been experimenting with multi-channel speaker set-ups; it’s a different way to experience sound and compose.

In my installation work I often use simple mechanical sound sources to build three-dimensional soundspaces. There are often hundreds of these spread around the architectural space. I started this type of work when I was doing a lot of multi-channel compositions. I recorded the sound of materials and did arrangements and compositions with them on the computer, playing them afterwards over several speakers.

As I was always driven by and interested in simplicity, reduction and directness, I then started to wonder how I could create such compositions in real time, rather than recording, processing and re-playing them. At that point I started to experiment with physical and mechanical systems to set materials in motion to generate sounds in a very immediate, direct and visible way. I have done visual works and experiments with acoustics since I was a kid, but in that moment both of these worlds merged together. You hear what you see and you see what you hear.

What was the first immersive sonic experience that really grabbed your attention?

[Laughs] That’s hard to say… I don’t remember, but I assume the first immersive sonic experience was probably even before I was born, sitting in my mother’s womb. There must have been lots of sounds around… But an early experience I do remember – I was probably about three years old, in the furnace room at my grandparents’ place.

There was an old oil heater, a very big machine. Being next to this huge, and at that age very impressive piece of machinery was exciting. The heater was working and making an intense drone – deep, dark and very physical. It turned off and slowly cooled down. While doing so, it produced these tiny clicking sounds as the materials were changing temperature, which reflected off all the walls in this small room. It was an amazing piece just perfect for a gallery…

Your installations are often referenced to architecture and you have worked with architects in the past. Where does your interest in the relationship between sound and architecture come from?

While most of my installations are site specific, the acoustic and visual spaces are core elements of my work. In that sense the architecture itself, is an essential and very influential element in the development of a piece. The sound properties of a space relate to its dimensions and its materialisation. It’s hard for me to imagine sound without a spatial context, or space with no connection to sound, or to develop an installation without knowing where it will be. In that sense space, architecture and sound always have been connected in the process of creating my work.

Are there any particular buildings which have directly inspired your work? And are composers like Iannis Xenakis an influence for example?

Great architecture is very inspiring to work with but there is not one single building that inspired me most. All of the spaces I have been invited to work with in the past have been inspiring and even completed the artwork somehow. Similarly to other creative work, in architecture I’m mainly interested in simplicity – in structures that have a deep sense of function, rather than just being decorative or fancy for the sake of it.

I can’t stand fancy fusion architecture which speaks so loudly but doesn’t say anything, or architects which try to make something extravagant looking which ends up being more of a self-actualisation project rather than an architectural one. Some timeless heroes of mine include Heinrich Tessenow, Sigurd Lewerentz, Kay Otto Fisker, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Arne Jacobsen and Klas Anshelm. Contemporary architects I appreciate include Tadao Ando, Peter Zumthor, or Sergison Bates.

Xenakis understood three-dimensional space as part of music, but I wouldn’t call him an influence. The artist that I was studying most in my teenage years was John Cage. I read almost everything he wrote. I see an influence in him, especially in the way he understood all kind of noises (and silence) as music. I liked his free and interesting form of thinking…

You’ve also released a few prepared motors (one alongside a cardboard box and cotton ball). How do you envisage these being used by the buyer and what made you want to make your materials public?

In between the series of audio releases we usually place single objects which do not relate to a specific series. Within those, I also placed two small works of mine, as you mentioned. They are both powered by a 9V battery and can be turned on by the owner. Once they are powered they start to move and to generate sounds that way.

Are these the kinds of tools you use when producing the records you’ve released on Leerraum? Is there an acoustic element like in your gallery work or are these done completely ‘in the box’, so to speak?

For my pure audio compositions, I usually work with recorded microsounds of various materials, as well as with sounds from mechanical experiments. Sometimes I even include some audio recordings from installations I’ve done. Next to this, I’ve been working on a series of collaborations for the past 11 years, where I use sounds from other artists to create multi-channel compositions. Within this series there have been collaborations with Oren Ambarchi, Kenneth Kirschner, Richard Garet, Helena Gough, Fourm, Asher, Andy Graydon and Mise En Scene. Currently I am working on one with Herman Kolgen.

Finally what’s next for yourself and Leerraum?

A beautiful thing about Leerraum is that it is small and fully independent, so we are very flexible. This means we don’t have to plan anything in advance. Once a work is ready, we can publish it within hours. We don’t even give deadlines to the artists we work with, so I can’t be totally sure what the next release will be right now.

Regarding my own work, we are currently getting ready for a solo show in a new museum – the Museum of Contemporary Art in Busan, South Korea. Today the last boxes got packed and shipped and at the end of the month we are going to Busan to install it. We will present two new site-specific installations in a huge space of more than 2000m² in total.

- Published

- May 23, 2018

- Credits

- Words by Theo Darton-Moore