Checking the Juice // Thomas Fehlmann

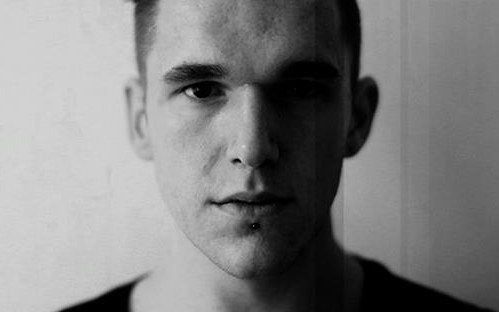

Photo by Max Zerrahn.

Thomas Fehlmann is many things: synthesiser-cum-trumpeter for early post-punk band Palais Schaumburg, minimal techno pioneer with the likes of Juan Atkins and Mortiz von Oswald, and of course a member of the Orb. But Fehlmann’s solo work is sadly less well known, although to my mind the strongest of all his output.

Fehlmann’s music has always appealed to me for a very simple reason: it swings. It may sound obvious but little techno makes use of swing in such a way. In some of his more mind-altering tracks, the swing is enough to throw you off balance, to wrong-foot the listener into a new rhythmical gait. What gives Fehlmann's beats their distinctiveness and longevity is the use of space between hits. Listen, for example, to how the rhythm slides into a new foothold on tracks like ‘Superbock’ from his brilliant Visions of Blah LP.

When listening to his work, it’s unsurprising that he draws influence from the Stones Throw crew and hip-hop in general. Producers like J Dilla and Madlib use tricks like these to stretch rhythms out of convention. The well-trodden 1-2-3-4 sequence of standardised rhythm becomes a warped matrix with which to play. Move the snare to an 'unstable' position, and suddenly everything is possible. Applying this approach from hip-hop, of freeing oneself from the tyranny of the 'quantise' button, Fehlmann gives techno a much needed lease of life. After all, if you ain’t got the funk then what have you got?

After nearly four decades in the game, Fehlmann described the process of writing his latest LP, Los Lagos, as ‘checking the juice’. An artist so entrenched in collaboration must struggle to produce solo work, especially after eight years since his last solo record, Gute Luft. To celebrate the release of his new record, we caught up with Fehlmann last week to discuss plants, J Dilla, and the legacy of techno.

Hi Thomas, how has your summer been?

In Berlin, we can’t complain. The only thing that is worrying for us is the drought for the plants. It’s been super dry, the driest I have ever experienced in Berlin. I suppose it’s the climate change.

I understand you’ve been making some music for plants too?

Well, funny you should say that. I was asked to do some piece but the botanical gardens in Phoenix, Arizona. It’s going to be installed in the next couple of weeks. I took ‘botanical gardens’ as a kind exotic inspiration — I am eager to be in conversation about plants because they are an important pastime of mine. I like the idea of music being surrounded by nature, or nature being surrounded by music.

I’m interested in how nature has influenced your sound. Your brand of techno has always struck as being more ‘natural’ or ‘alive’ than some of the more industrial contemporaries.

I take this as a compliment, thank you [laughs]. This is my take on it: I am always trying to make groovy stuff, and my interest in nature allows for the techno to be a little bit… softer. I just go where the vibe takes me, and I am often entertained by techno that has swing and groove and funk and so on.

Techno is often seen as a genre of convention — from classics synths to the formalistic structure of DJ tools. But I often feel like your music is more rebellious than that.

Yeah that’s how it came into my life. I wanted to push against existing boundaries. After all the ‘boundaries’ are usually imagined, they’re not really there. So I want to have a close look at these hidden boundaries, and whack them about!

Photo by Max Zerrahn.

Photo by Max Zerrahn.

Do you find traditional electronic instruments limiting in that sense? Is it harder to produce swing with a drum machine?

No — it ain’t [laughs]. With drum machines in the 90s, you even had a special button to actually adjust the swing. These days, I obviously use machines and synthesisers but in a way Ableton Live is the main source of controlling, developing, hacking up sound. That gives me a pretty broad control of producing ‘natural grooves’. You don’t have to quantise if you don’t want. I like sound that flows and slides around. Think about J Dilla, for example. He made some of the grooviest beats of all time, but he didn’t care for the quantise grid. It was an amazing experience hearing Dilla for the first time, it was like an approval of the kind of sound I had been after for years! Some of those beats give me goosebumps.

Madlib is another one.

Yeah — I love his work. I included some in my recent mix for XLR8R. I actually had the chance of meeting the man a few times. We had an artist chat at one point for a magazine. He actually turned out to one of my gigs in LA, that was kinda hot…

Do you record your takes live, where does that ‘live feel’ come from?

If I do some sequences on an old hardware machine, like an old Korg, I do treat them like a sample. I’ll cut things out, re-quantise… What I don’t like is this idea of sitting in front of a keyboard and playing a melody, so I’ll always try to fool myself into making melodies out of samples of my own playing. I got quite frustrated with this traditional concept of sitting down and playing a line of music. My fingers don’t surprise me any more. So I always rely on process to get a structure going, to get some melodic content.

Is that down to ‘happy accidents’ then?

Well you set parameters for yourself, and these parameters cause mistakes, some of which sound very good. I teach a class of students at the moment, and the main theme of the class is ‘happy accidents’ [laughs]. We do group improvisation, which is a rare thing in electronic music today. We sit around a table and do ‘rounds’. A ‘round’ includes every member of the group possessing a simple noise or tone or sound-element. We wouldn’t know what our neighbours would do, but we would nonetheless fire off our individual sounds in a round after one an other. After a while, you build a foundation of happy accidents, and this is very fertile ground for new ideas.

Do you incorporate these ideas into your collaborative work?

When do I collaborations, such as my recent work with Terrence Dixon, I much prefer sitting together in a shared space instead of sharing files over the Internet. I tend to listen to music differently when there is two pairs of ears in the room. In the case of The Orb with Alex Paterson, we also worked really fast because we had a good understanding of what we were doing and very little need for questions between each other. There was a natural flow and that is something I really enjoy.

Are you planning any more Orb stuff in the future?

Well who knows — never say ‘never’, right? It’s clear that Alex [Paterson] chose to go in a direction that doesn’t necessarily match so well with my intentions. It just became a question of where flexibility would become compromise. I wasn’t quite up for that and it was just very obvious that I couldn’t help him with what his fantasies were. So I therefore thought it would be better to let him follow his dreams, and I mine. This happened before with the Orb: there were always phases where we were closer, and phases where we were further apart. As long as you’re able to handle it in a grown-up way, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.

I was very excited to see that you had done some work with Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry.

Yeah [laughs]. That was out a series working with Alex’s main influences. It was clearly Alex who brought that idea to the table. It was also good that I was involved because he was so star struck [laughs]. Obviously I have big respect for the man but I didn’t find it difficult to talk to him. He came round our house in the countryside, we sent ourselves a week to work, we expected to do maybe 4-5 tracks but we all got so fired up that we made two albums’ worth of music.

People must be very jealous of that.

Yeah well when you’re in the middle of the storm, you don’t notice the wind around it [laughs].

You described the making of your new album as ‘checking the juice’, what does that mean?

Well ‘the juice’ is like the most precious thing you have — the juice from a flower or an orange. Checking the juice is just seeing how much sugar essence or orange juice is left, you know? Another analogy would be ‘kicking the tyres’: you kick the tyres before a big journey to make sure everything is working and in good condition. I haven’t really done solo tracks for quite a while. When I was working with Alex, he had so much material to give that I could hardly stop him [laughs]. When I got back into the studio alone, it was like looking in the mirror, I was the only source of material available. Checking the juice is like testing yourself: can you still do it? You have to prove it to yourself everyday, anew.

Would you say this was a particularly difficult album to make?

Before I started recording, it was difficult. Because I had to get so many things out of my system, such as the last seven years with the Orb. But the album was actually much easier to make than expected. As soon as I started, I felt a good drive to it, and I was finished in a month! So the juice is still fresh [laughs].

Who made the artwork?

Albert Oehlen — he used to be a fellow student of mine in the 70s, and went on to be on the fucking excellent new painters. When I look at his paintings, I often feel like he uses space and colour in the same way I use time and sound. He has a given space that he uses to fill up with colours, and I have a given time than I am filling up with sound. He has a great way of mixing high and low art, which is something I feel very connected to. It’s why I like using very kitsch-y sounds with very gritty sounds. Sometimes I look for drum sounds and I think ‘agh this doesn’t sound shit enough!’ Sometimes I want to find a really shit-sounding thing, and take it out of context to make sound it good again. This is the kind of ugliness where bad becomes good.

I also like your use of the word ‘techno’ as a verb: to techno, as a kind of process.

Yeah because it totally is, man! That’s how it works for me. It’s obviously not limited to the bang-bang-boom club culture. Techno is a way for me to treat my machines and a way to draw out inspirational and fun music. If you really want, you can say ‘to techno’ is to make art! Techno is a form of art for me, and I am always stunned by how many different shades of the genre come out each year. What was expected to last only three years is now with us for nearly three decades. This week there is a big celebration of the techno’s longevity in Berlin. 1988 was the year this Detroit techno compilation came out on 10Records — that had a very big impact on me at the time. We were certainly doing stuff during those days but it wasn’t what you would call ‘techno’. But that’s the thing — with music you can only ever try to fulfil the fantasy in your head with the stuff you have around you. When Juan [Atkins] started making music, he said he wanted to sound like Donna Summer. He failed, but how brilliant was that failure!

'Los Lagos' is out now on Kompakt.

- Published

- Sep 14, 2018

- Credits

- Words by Georgie_McVicar