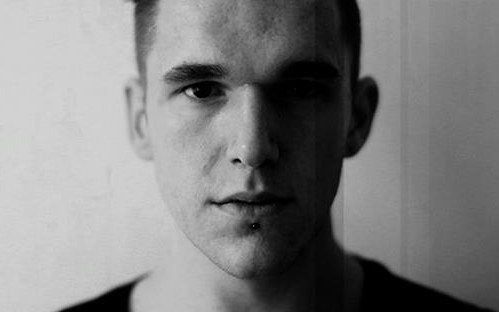

The Rebirth // ZULI

Ahmed El Ghazoly, aka ZULI, meets me in a cafe during Unsound. His new album, and debut LP, Terminal was to be released in November on Lee Gamble’s label UIQ. Judging from his publicity photos, I imagined to be meeting someone serious, frowned, if not a little intimidating. But I couldn’t be more wrong about what he’s like. El Ghazoly struck me as a soft-spoken and courteous collocutor, who soon began asking questions in return and on my attempt to draw the attention back to him, noted that “we are only halfway through the salads”.

In Cairo, he’s known as one of the leaders of the underground music scene. The club VENT he was running with the group of friends was responsible for bringing international DJs to the city, as well as introducing Egyptian DJs to the world. The cultural exchange is present in his music too: his set at Unsound was a mix of techno and jungle, while Terminal blends genres like breakbeat, hip hop, trap and ambient to a somewhat deconstructed effect. “Many of us who don't fit into any one specific group identity feel sidelined at best”, writes El Ghazoly in the album’s description. Growing up in the UK and now living in Egypt, he speaks up about the exoticism of Eastern music and culture, which pigeonholes people into the roles he doesn’t want to play.

During our lunch in Krakow, we chatted about the importance of collaboration, new album and future plans, local scenes and putting music first.

You say that sounds aren’t connected to the geographical locations anymore, but I can think of a few artists whose music can be described as having such local quality. What do you think?

That’s something you can consciously do. I don’t want to assume anything, but I feel like a lot of people consciously do that, especially where I’m from, in Egypt. You can tell that it’s not genuine. For instance, you see someone from rich areas making street music, but there’s no way you grew up like that, I mean, you can’t even pronounce Arabic properly, because you went to an international school. You can tell that in the vocals but Europeans, they don’t know, because they are listening to Arabic, it’s just Arabic.

There is a lot of dishonesty. I know that for a fact, from the Egyptians I’m telling you about. I understand why they’d resort to that because it’s very attractive to promote us abroad, promote us more like a concept. It sells, I guess. There’s a movement in Egyptian music called Mahraganat, or Electro Chaabi as they call it sometimes, so that’s been massive since 2008/9 and it’s been steadily growing. The amount of musicians who’d switched to that just because it’s successful and because it’s easy… Nah.

How do you think the revolution of 2011 affected the music scene in Egypt? I’m speaking from personal experience, as in Ukraine the party scene has grown significantly after the turmoil of events.

Honestly, what we’re doing, in terms of the circles I operate in, it has very little to do with the revolution. I mean, of course it has — we were there at the time, so of course it has in some way or another — but it’s not political. I mean, everything is political, kind of, but it’s not specifically like “oh this is resistance music”.

The only effect on music it had was mainly in instrument-based music, like rock bands and stuff. All of the sudden they were all singing about the revolution. Empty slogans, very generic stuff. If anything, the revolution was bad for the music scene. It did more harm than good, honestly. A lot of bands that had potential stopped developing. They just went… “alright, this is what sells, this is what makes you successful, let’s sing about the revolution”. How patriotic and revolutionary are you if you’re signed to Coke, and Pepsi, and Vodafone, and you do ads for like Range Rover. Come on. Don’t call yourself a revolutionary band.

What’s the underground scene like then?

It’s a bit tricky because when you think about the funding and where it comes from… Obviously, it costs money to put on parties. Who’s gonna pay this money? Most of the time it’s British Council or other cultural institutions like that. Most of them can’t support things that have alcohol consumption and most of the cultural events, not just music, are funded by these bodies. They have a quote each year to spend on culture, I think. The corporations copy them saying, “we can fund you also and we allow alcohol” but they want to sell.

So, it’s never really about the music: it’s about either what those institutions think music and art should be or what the corporations think will sell, what their type of audience would be. Then, you have a different class of Egyptians who can afford to spend money, but their taste is not… great. I mean, it’s like everywhere in the world. They don’t really like underground music, they are more into tech house music. So you have booming tech house scene in Cairo. It’s massive. They are doing really well.

I’ve read that some nights at VENT were quite expensive. How accessible were they to the majority of people?

On some nights we had to do that, yeah. We used to charge on the door on the club nights on Thursdays and we would book some of those tech house DJs. That’s the only night we’d make money. This allowed us to lose money throughout the week and book people who have no following. We debuted like 40 artists. So, we’d charge a lot on the door on Thursday, because these were like fancy people and then we’d lose it all. Most of the nights were free, but one other night was 50 [Egyptian] pounds, which is a third of what we would charge on the club night. It’s the only way we could survive.

Did the underground scene grow in size over the last couple of years?

For the dance part, yeah even the experimental dance part that we operate in. For the live performances, I don’t think so at all. Because there’s been no one putting on live nights really. There was this one series, but it was mainly the promoter’s friends and stuff. Attendance...what? 30 people, tops.

Your new album Terminal is less for dancing, but more for listening. Why did you decide to change focus?

That’s actually a bigger part of what I do and I feel like all the records I’ve put out don’t reflect that at all. At some point, I just felt like I have a lot of this material that I’d like to release, so I spoke to Lee about it… because I always go to Lee first anyway. I was like: “Listen, I’ve got an album I want to put out, I know you don’t do albums, I’m just telling you”. It was perfect timing, because they were actually thinking about releasing an album. So I used some of that stuff. At first, I wanted it to be specifically non dance, non hip hop, just like beatless, ambient stuff. But over time Lee convinced me to let got of the idea that it needs to be so rigid, and that was a good idea, because then I ended up blending these things in some of the tracks.

The album features a lot of different vocalists and you were, and still are, a part of different collectives. Can you tell me about AHOMA, for instance?

AHOMA is dead. Unfortunately, it was very short-lived. AHOMA was supposed to be a collective of musicians, visual artists and promoters, so that we could all book each other, like a very contained scene. It was all about the money really: so the money would go around between all of us and the scene would kind of organically grow. The idea didn’t sit well with a lot of people who wanted to be like: “I’ve got an opportunity to play at this club, why can’t I play there?” And the idea was: while this club may never book this person from AHOMA collective, because they aren’t popular, they’ll book you, because you have a review somewhere and you’re good for them. But we wanted to support everyone, which is why a lot of people were like: “No, I don’t want that, I want what’s best for me”. It ended a couple of weeks before or after CTM, so February or March. And we started in December.

You seem to enjoy collaborating with other people. Why so?

I started out in a band environment. I always wanted to be in a band, but then I eventually let go of the idea of collaborating on the music itself. There’s a lot of really talented musicians in Cairo. I feel like they need to be heard. It’s not going to happen if each one of them works on their own. It’d be a shame not to help each other out and grow together. It’s a bit idealistic and it doesn’t work all the time, but at least we try.

In the description of Terminal you write that it “draws from an abstract narrative of increasingly frequent cycles of ego-death and rebirth”. What do you mean by that?

Literally that, on a very personal level. Life is all about learning, cycles. And the more you learn, the more you realise that you don’t know anything. When I look at the past, I can more or less see that it was a cycle and it’s done — I came out of it and that person died, that version of me died and I came out of it with this lesson. That’s the rebirth. And then you go to another cycle and then that person dies and so on.

What about working with visual art? You did an installation for CTM, is it something you want to continue doing?

Yeah, I’d love to do more of that. I’d love to do more installations in general, maybe not even specifically visual art. I’d love to move away from the dance floor and make less dance floor stuff. I mean, I do like dance music, but I also love experimenting with sounds. I feel like installations is a good way to do that, because you have a concept and it’s not entirely loose which I’m not a massive fan of, you know, music that’s entirely loose and aimless. Not a big fan of concepts either, but I think this is like a middle ground.

In terms of the visual arts, I only shot the video for The Magma and someone else edited it — a really good video editor from Cairo, he works mainly in ads, it was his first time doing anything like that — but ideally I’d like to learn video editing myself. Not sure how I’m going to have the time to do that, but I definitely would like to work more with visuals like that and hopefully incorporate them into my live show at some point.

I still like making dance music, but I feel like I’ve only done that so far, more or less, with the records that’ve been out. It’s more challenging and rewarding at this point to me to make music that isn’t made for the dance floor. I like melodies.

Have you had a chance to explore much of Unsound yet?

The Moor Mother thing was amazing. The drummer was like a machine, the control he had… and the bass player, they were so sync when put together. I really enjoyed that. I also went to the TCF’s discussion about swarm producing. That was really interesting, it’s a nice idea. I haven’t managed to see anything else, because I crashed as soon as I got here and then I woke up and went to Moor Mother and that’s it.

Ahead of the festival I spoke to Renick Bell, who has released on UIQ as well. I know you studied Computer Science, have you ever wanted to try live coding?

Yeah. It’s definitely at the back of my head. It’s one of those things: if I have the time, I’m definitely going to learn how to do this. Seems really interesting.

Have you ever worked as a programmer?

No, not for a living. I was kind of good at it at the university. We used to write video games and stuff. We did a lot of AI. Then I graduated and I wanted to be a DJ. I’m still very interested in coding and dealing with machines in general. But when you’re at that age — I was in the university between the ages of 18 and 24 — you’re not entirely sure what you want to do with your life. I did try to get some jobs, but besides the coding all my grades in university were really low. I barely went. I was out partying most of the time. I was a promoter at the time also, so I graduated with a really low GPA, couldn’t get a job and was like: “Fuck this, I’m just going to continue DJing”.

So, you’ve never had like a formal job?

I did customer service for Vodafone for either three weeks or three months in 2008. It felt like three years. Hell. It was rotational shifts and I had set working hours. Some days I’d wake up at four in the morning, go to work, which is on the other side of town, finish work, come back and I had to sleep. It’s just… Nah. It’s not a life. Then, I did a lot of translation jobs, freelance, so I could also work on music at the same time. I did some IT work but I’d go into the office whenever they’d need me. I was also doing music at the time and I quit because I was in a band and we got SXSW. Music always had the priority.

What do you think about the theme of this year’s Unsound? Presence not in a sense that we have to forget about the technology, but as a way to incorporate it in our lives sustainably?

It’s a perfect way to look at it. It’s better than a purist approach of letting go of technology completely. It’s a more realistic one. It’s very important to be present. I’ve struggled with that a lot. You know, when you spend most of your day looking at the screen, it’s very difficult. This mind-body connection thing is not a joke. So dealing with it responsibly is very good.

You have a show on NTS so you must visit London often or… No? Do you record it in Cairo?

Yeah, I’ve only been to London three times in my whole life. I used to live there as a kid, but in the past ten years, I’ve been there three or four times, yeah. I’m going there next week.

What’s your impression of it?

The scene is great, the music is insane, the options… quite a contrast with Cairo. The problem in London is “what am I going to sacrifice tonight?” That’s such a contrast with Cairo, it’s insane.

I have this soft spot obviously, because I was there as a child, so I have this thing that I can’t really verbalise, the smell and everything. There’s something about London that I like, but when I think about it rationally: it’s so expensive and there’s ads everywhere, it’s like capitalism on steroids. So, that part I’m not in love with. Piccadilly Circus is probably one of the worst places in the world. It’s up there with the Times Square I think, but considering all I’ve just said, London would be a very nice place to live.

When I moved [to Cairo] from such a different environment as a kid, I adopted this “no” stance, like everything around me is wrong, no: I’m not from here, I don’t belong here. I feel like that’s the kind of attitude that stayed with me on many levels maybe.

Would you ever consider moving back there, if you could? Or are you happy to stay?

I’m actually quite happy down there. Not sure happy is the right word, but there’s a lot of things I’d like to stay for. The secret project is one of them and that’s just right now, maybe it never happens, maybe it fails. My parents are getting old, I’d like to be close to them, you know, be present. I visit them more often now and I wouldn’t be able to do that if I lived in another country.

Another thing, a big thing actually, Egypt’s really cheap. I pay peanuts for rent, man. I have a big flat on my own and my rent is 3500 Egyptian, which is like 160 euros. For the entire flat. So, I wouldn’t be too quick to move. And, this means I can afford being a musician full-time. I gig in Europe or whatever, I come back and I don’t have to work for 6 months sometimes. That’s something important, that’s not something small.

Do you have any plans for the development of the scene in Egypt?

You trying to get the secret out of me? [smiles].

Aha… But is that something you want to do?

Yeah! It’s not necessarily because it’s Egypt and I’m Egyptian. It’s because I know specific people, who are really really good and they deserve to be heard. They are really really great, and not just producers, also DJs. For instance, for my NTS show I started the series now for my favourite DJs from Cairo, The Nile Sessions.

It’s great to see someone trying to showcase the overlooked talent like that. And you really seem to want to separate your activity from geography or politics.

At the end of the day, I’m not a specialist. I’m a musician. I have political opinions like any civilian has political opinions. I’m not qualified to do political commentary and then, everything is political anyway. So, what I mean is that just because I’m from a certain place doesn’t mean I have to sound a certain way. The geography doesn’t matter that much in 2018 and yes, this album is about my life in Cairo, but I would make it anyway if I was living somewhere else. It’s more about my life than it is about Cairo. It’s about Cairo’s effect on me.

I think a good way to paraphrase would be this. That installation I did, The Magma, that is about Cairo. I couldn’t do it in another city because it’s specifically about Cairo in 2018 and how people are boiling. They can’t stand it there, but they are never going to do anything, which is where the metaphor comes from. Magma is a type of lava but the album is about my experience and my surroundings that just happens to be Cairo. Part of the creative process is the isolation and the creative process drives me crazy in a way... So, I would have made the record anyway, but if I didn’t live in Cairo I would have never made The Magma, the installation.

Do you find the isolation helpful?

I think it’s necessary for me, but psychologically it’s not good. It’s very heavy and it informs your lifestyle in a way that isn’t very healthy. Yeah, that’s that. Kind of like: I need to do this, but it’s bad for me. That is a big part of the album, I think. That, you know, I can do it, but it is not good for me.

What kind of isolation is it?

I don’t even go out of the house. I could, I do, stay in the house sometimes for months. My gym is downstairs, two streets away, supermarket and gym... Sometimes I go out and visit my parents. My girlfriend is very understanding: she comes and visits me. Whenever I can, I visit her. On my way back, I visit my parents sometimes. That’s it really. If I’m not fully immersed in making, it’s not the same. There’s a specific level of detail that I can’t really pay attention to if I’m like going out, and seeing people, and socialising. That’s just me, it’s just a very personal thing. I’m sure it’s not the same for most people, it’s how my mind works.

Is there anything else you want to say about the album that we haven’t discussed?

I think we already have a bit, but it’s very personal. The most personal thing I put out to date. The thing about instrumental electronic music is that you aren’t contained by language. You can express things you can’t really verbalise. When you don’t have to verbalise and you don’t have to make people dance, it’s very honest.

'Terminal' is out now on UIQ.

- Published

- Dec 6, 2018

- Credits

- Words by Maria_Ustimenko